J. Philip Hyatt, Jeremiah: Prophet of Courage and Hope. Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1958.

J. Philip Hyatt, author of Jeremiah: Prophet of Courage and Hope, died in 1972. During his life, he published extensively on a variety of topics ranging from Ancient Near East languages to biblical exposition, and even contributed the Jeremiah entry to the Encyclopædia Britannica. From 1944 to his death 1972, Hyatt served as a professor of Old Testament at Vanderbilt University. While there, he published books and articles on the humanities, but particularly on studies on the Biblical book of Jeremiah. In particular, he contributed to The Interpreter’s Bible rom Abingdon Press, which was published in 1956.

In Jeremiah: Prophet of Courage and Hope, Hyatt brings together the threads from his previous work, as well as lectures given at Texas Christian University in 1954, to craft a readable survey of Jeremiah. Rather than taking a straightforward approach, consisting of introductory material and a verse-by-verse exposition, Hyatt opts for an approach that seems haphazard at times. Still, the book’s ten short chapters offer an illuminating look at Jeremiah and the world that he inhabited.

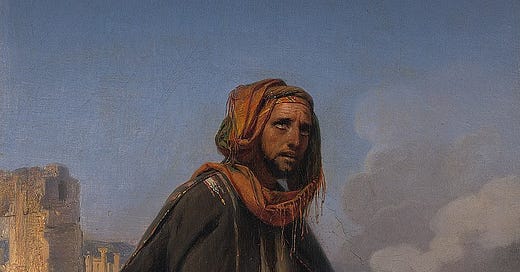

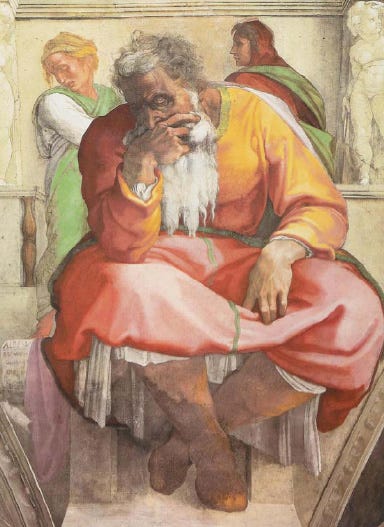

The first half of the book deals primarily with the historical elements of Jeremiah’s life and times. Hyatt spends chapter one defining a prophet in Ancient Israelite culture, shattering some of the misguided stereotypes that accompany the idea of a prophet. These men were sometimes poets (14). Some of them may have had ecstatic experiences, but by no means all of them (19) And each prophet was a regular person in some respects, dealing with very real problems in life (20). Jeremiah also lived during exciting times in the Ancient Near East, with the fall of Assyria, the rise of Babylon, and the reforms of Josiah in Judah. Shortly after Jeremiah’s death, Buddhism, Confucianism, and Zoroastrianism would also get their start (30). Of course, this larger picture served in some ways as the tapestry for the turmoil in Jeremiah’s private life as well. Though likely from a priestly line, he did not serve as a priest and frequently found himself at odds with the religious leadership of the day, including his own family (32). Jeremiah’s middle years were fraught with warnings and doses of reality, both for those at home and those who were already in Babylonian exile (49). Even after the siege of Jerusalem in 587 B.C., Jeremiah continued to warn the people to submit to Nebuchadnezzar, whom Jeremiah perceived as the servant of God (59). Having spent time in prison, and eventually finding his way to Egypt with some of the Judean survivors, preaching for them to repent of their idolatry until late in his life (60).

Beginning in Chapter VI, Hyatt turns towards a different approach to understand Jeremiah. He starts with the personality of the prophet, highlighting the tenderness of Jeremiah which is easily found in the poetic portions of his oracles, like in 20:14-18 (63-65). Though known as the “weeping prophet,” Jeremiah also experienced moments of great joy (67). It also here that Hyatt addresses his title, demonstrating the courage of Jeremiah through passages such as 26:14-15 and 37:16-21 (71-73). Jeremiah refused to take the easy way out of tough situations, like telling the king that his expedition is doomed to failure or that his reign is ending, because he was confident in the powerful goodness of God and that to remain faithful to his Lord was what such situations called for. As a faithful man of God, Jeremiah was an active theologian, dealing with the Lord in a real, living manner, while also prophesying things of theological significance. The theological concepts of God’s sovereignty and His love both find voice in Jeremiah’s oracles (82). Hyatt then wrestles with Jeremiah’s individualism and the New Covenant, noting that he does not go quite as far as Ezekiel nor does Jeremiah reach the New Testament teachings on such matters (97). Chapter IX rounds out Hyatt’s examination of Jeremiah’s message, and the title, by focusing on the concept of hope found throughout the prophet’s oracles. Jeremiah was supported by two main ideas in this hope: God’s purposes and the possibility of man’s repentance (99). With his final chapter, Hyatt lays out a few brief “values” that are present in Jeremiah, and highly relevant for the people of God today: 1) understanding that God’s servants are real people, who sometimes fall and mess up, 2) recognizing prayer as a dialogue with God, 3) recognizing that true religion is always concerned with the inner parts of a person, not just the exterior, 4) seeing that God has always been a God of love and that He is still active in history, 5) realizing that repentance is the first step towards active service to God, and 6) that true hope, based on participating in life, is never disappointed (109-115).

The book is a short, insightful help in sifting through one of the most complex books in the Old Testament. Still, it is not without some areas of contention. One of Hyatt’s most interesting claims is simultaneously his most difficult to accomplish: aligning the prophet’s oracles with the chronology of their life (12). Though Hyatt provides a helpful appendix to show what he means, there seems to be some room for debate regarding the exact chronological sequence that he lays out. And for prophets who have less biographical information, which is essentially all of the other Old Testament prophets, this task becomes even harder. Additionally, Hyatt questions the written history of Jeremiah at several places, at some points thankful for the Deuteronomist’s preservation of biographical information, but at other times rejecting what Hyatt perceives as additions (39). These are minor quibbles in what is otherwise quite a helpful book.

Of the biggest issues at stake is Hyatt’s treatment of the New Covenant idea found in Jeremiah. Though Hyatt points out that individualism is not something Jeremiah invented, the brevity of his summation does leave adequate space for him to interact with ideas that build on Jeremiah, such a Reformed theology’s covenantal approach (87). Hyatt even manages, through his focus on the possibility of man’s repentance, to avoid any of the sort of free will debates that often arise out of studying this prophet. As such, he does not say anything that causes great offense to either side, but neither does he delve deep enough into the modern theological discussions to weigh in on the matter in a significant way. This is the charm of the book (Hyatt’s ability to briefly deal with complex issues is worth imitating), but at the same time leaves the reader wanting much more than is offered. And this is the grand plan in the end: to the reader who has tasted of Jeremiah’s depth and wants more, Hyatt’s work on the Interpreter’s Bible will have to fill in any of the gaps that remain. Hyatt does everything that he sets out to do in his introduction and does so with clarity and grace throughout.