Donne's Ineffectual Speakers

A Brief Look at "Elegy Nineteen" & "The Flea"

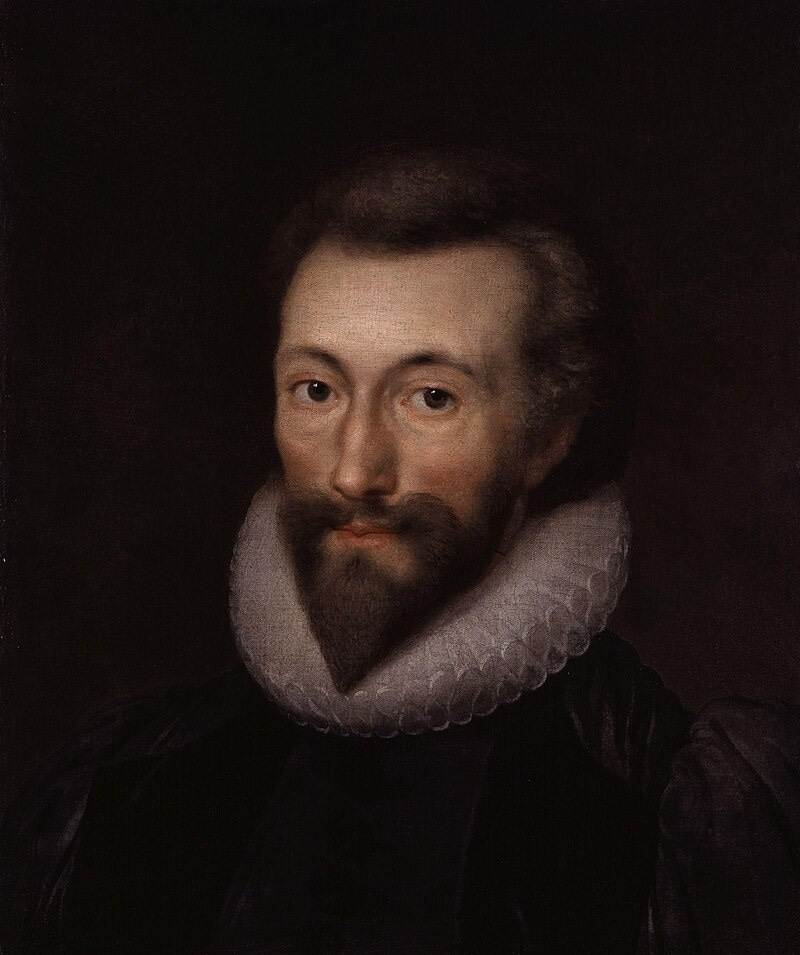

This is one of my earliest attempts at close readings, focused on two poems from John Donne. I was reading a lot of Early Modern English authors at the time, with Donne and Milton being the most prominent presences in my library. I was initially drawn to Donne because he seemed to have fallen out of favor in English departments due to his overt Christian themes. I don’t know if this is still true, but Donne continues to be a source of comfort and encouragement to me today regardless of his status in collegiate administrative offices.

. . . and so it was for John Donne, who was born into a world which, like our own, was rapidly moving out of its own past through the agency of a violently agitated present into an uncertain and only dimly apprehended future.

Robert S. Jackson, John Donne’s Christian Vocation (1970)

John Donne is a poet often left out of literary studies. His poems, with their bizarre and violent images, have puzzled scholars for hundreds of years. Interpretations of Donne’s love and devotional poems have ranged the entire scale of poetic understanding only to leave scholars conflicted and without any concrete idea of what Donne was really trying to do. I believe this confusion stems from a misunderstanding that readers since Donne’s own age have fallen prey to. As Germaine Greer points out about “Elegy Nineteen:” “the contradictions are relentless,” and I would argue that these same issues are the tool that Donne uses to explore “the contradictions of the human condition.” As Donne grappled with his understanding of the exponentially changing world around him, he forces his readers to grapple right along with him. Donne shrouds his meaning, but still his purposes in writing are there within his verse.

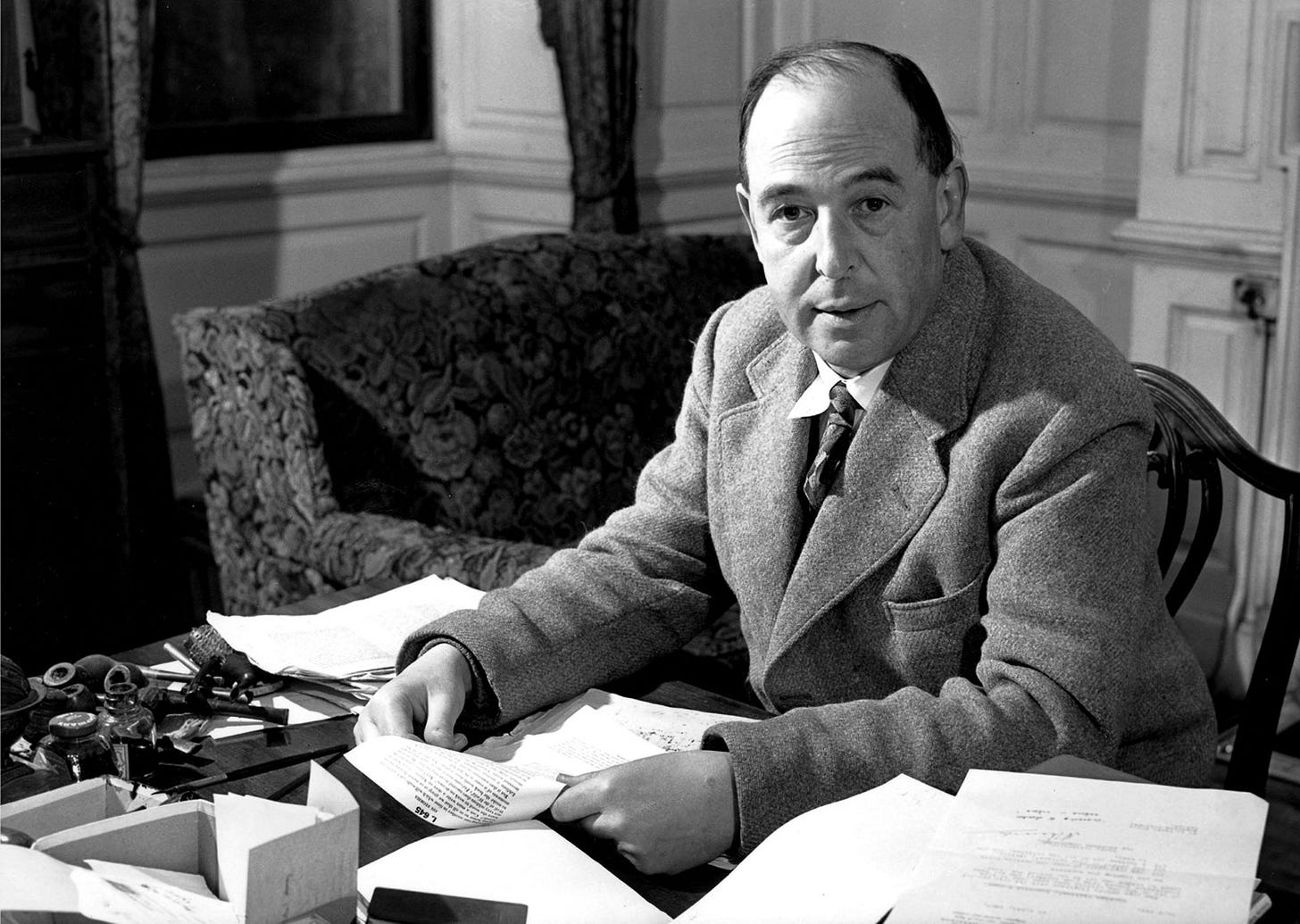

“Elegy Nineteen” and “The Flea” are two of Donne’s most widely recognized poetic works, and their meanings are as popular to debate. The reason, I believe, that these poems are so difficult to pin under a unified interpretation is Donne’s use of the ineffectual speaker. Donne does not put himself in the place of his feeble speaker but makes use of that weak voice to wrestle with a changing world where love, religion, and life were being put under a microscope. C. S. Lewis points out that Donne’s poetry feels very much like a reaction against “the great central movement of love poetry . . . represented by Shakespeare and Spenser” (115). It is that questioning spirit that Donne latched onto to examine the traditions of his day.

Looking at “The Flea,” some have read Donne’s humorous poem as an ingenious argument to demonstrate how chastity is overrated. The speaker in “The Flea” may be capable of clever rhetoric, but Donne’s poem does more to protect chastity than to dismantle it. Donne sets the reader up by using the flea to make his initial argument:

And in this flea our two bloods mingled be;

Thou know’st that this cannot be said

A sin, or shame, or loss of maidenhead. (lns 4-6)

Although the flea was a standard erotic symbol for poets, Donne’s use of the insect is in no way traditional. The speaker places his own life inside that of the flea, elevating the flea and reducing the value of the speaker. The humorous comparison undermines the efforts of conniving that are being exerted. And even though the poem is considered a love poem, the object of the speaker’s passion appears only once, when her “Purpled . . . nail” squashes the flea that contained her own blood (ln. 20). With that singular emergence, the woman whose chastity is being challenged crushes the very foundation of the speaker’s argument, and simultaneously destroys a part of the speaker himself.

Although his cause is hopeless, the speaker seizes upon the death of the flea to point out that

Just so much honor, when thou yield’st to me,

Will waste, as this flea’s death took life from thee. (lines 26-27)

Since his argument made no dent in the woman’s resolve, the speaker makes a final effort to trivialize the intercourse he is seeking so heavily by now comparing the loss of honor to the death of his elevated pest. By even mentioning that the sexual union he is seeking brings a connotation of the “loss of maidenhead,” the speaker is again undermining all his efforts (ln. 6). Donne’s “The Flea” belies a perspective that holds virtue in high regards. The speaker becomes so enamored by his pursuit that he fails to even recognize his “beloved” until she destroys his patron insect of sensuality. The poem provides opportunities to laugh, but at the expense of the imprudent beggar whom Donne gives a voice.

Greer proposes a similar reading of “Elegy Nineteen,” claiming that the poem “is not written to a woman, [nor] is it a negotiation with a woman,” but is instead about a husband and a wife and explores the conceptual and actual contradictions in a marriage (222). Lewis also comes very close to this understanding of ‘Elegy Nineteen’ when he says:

Nor would I call it an immoral poem. Under what conditions the reading of it could be an innocent act is a real moral question; but the poem itself contains nothing intrinsically evil. (117; emphasis mine)

Greer’s argument hits the nail right on the head and sheds tremendous light on a poem that has been incorrectly subtitled by publishers, “To His Mistress Going to Bed.” As Greer points out, the mere fact that the “mistress” is going to bed implies a ritual, something that happens on a regular basis and within the bonds of marriage. Donne’s speaker begs,

License my roving hands, and let them go

Before, behind, between, above, below. (lines 25-26)

The pleading sounds like a privateer beseeching the Queen, according to Albert C. Labriola, and therefore gives the impression of man bound by wedlock rather than a man seeking his harlot (qtd. in Greer 219).

As Greer elaborates: “it is Donne’s achievement to strike [the reader] with the wonder and elation produced by the lover’s mounting sexual excitement” (220). But that very wonder is shattered by the concluding question of Donne’s elegy:

To teach thee, I am naked first; why then

What need’st thou have more covering than a man? (lns. 47-48)

The efforts of Donne’s speaker are frustrated by a wife who comes to bed clothed. Perhaps she did not hear her husband when he exclaimed,

Full nakedness! All joys are due to thee. (ln. 33)

Or maybe she did not want to listen when the speaker tells her,

Off with that girdle, like heaven’s zone glistering, / But a far fairer world encompassing. (lns. 5-6)

Greer points out that it is unclear whether the “mistress” is even paying her husband any attention, but the result is a frustrated man who sought to enjoy the physical relationship he should be sharing with his wife. Through the poem, Donne explores sanctified relations within holy matrimony. Using the poetic language of the love poems popular during that time, Donne frustrates the reader and the speaker by abandoning the “pornographic poem” at the crux of its scene (Lewis 117).

In both poems, John Donne forms an apparently strong argument and puts that argument into the mouth of a speaker who sounds like the many lovers who have come before him. But then, Donne ends the poems in failure, but not failure of the “unattainable mistress” type. While “The Flea” questions the consequences of freely giving love outside of the bonds of marriage, “Elegy Nineteen” criticizes the belief that sexual union within a marriage is always given freely:

To enter in these bonds is to be free. (ln. 31)

Donne looks at both sides of the proverbial coin when examining the marital practices of his day. These two illustrate the pattern of Donne’s poems. The apparent confusion caused by the witty organization of his poems in truth is an exploration; it is a way for Donne to tackle deep spiritual and moral issues that were widespread in the England John Donne inhabited.

Greer’s analysis of “Elegy Nineteen” rightly highlights the puns and contradictions to reveal a poem that is “so teasingly ambiguous that learned critics have on one hand seen it as Donne’s epithalamium for himself and on the other refused to accept it as having any relevance whatsoever to marriage” (222). But I do not think that ambiguity is the whole of Donne’s poetry. There is something attractive in Donne’s poetry. As I heard another student once say, “Once you’ve read Donne’s poems, you can never forget them.” And it is that lasting element that makes his ineffectual speakers drive their readers to confusion. An individual may read Gulliver’s Travels and understand from the beginning that Swift never intended Gulliver to be trusted. But Donne’s speakers, whose intense imagery and poetic ideas are burned upon the reader’s mind, do not have that same overwhelmingly dishonest appearance. The first time a person reads “The Flea,” they may be very inclined to nod their heads and comment on the excellent point being made. But that is the beauty of Donne’s work. As he wrestles with sexual desire and spiritual battles, he beguiles his readers to the point that they must read carefully.

Donne’s poems showcase a soul caught amidst a torrent of cultural strife and religious upheaval. It is that turmoil within the context of John Donne’s everyday life that I believe caused his severe choice of imagery. Lewis again proves helpful here: “No one . . . expects lovers to be compared to compasses; and no one, even granted the comparison, would guess in what respect they are going to be compared,” (110). But even when Donne uses images standard among his contemporaries, such as his use of “this flea” whom within “our two bloods mingled be” and “my America! My new-found-land,” he does not treat them the same way other poets of the time did (ln. 4, 47). He rejects the standard conventions, tumbling towards the very things that a future audience would crave. In all this observation, Lewis raises perhaps the most salient point about interpretive approaches towards Donne’s poetry:

We, like Donne, happen to live at the end of a great period of rich and nobly obvious poetry. It is natural to want your savoury after your sweets . . . We want, in fact, just what Donne can give us – something stern and tough, though not necessarily virtuous, something that does not conciliate. (112-113)

Those qualities of Donne’s, the disagreeable images, and hard arguments, are the truly rewarding portion of his poems. Readers today can pick up one of Donne’s elegies and they will see something gritty, something that despite its bizarre nature resonates with the individual on a very real level. Donne’s ineffectual speaker may cause debate and confusion, but it also allows Donne to reach out to an audience centuries after him. Donne achieves his massive effect on this generation by presenting the reader with a speaker incapable of making any effect at all. The ineffectual speaker makes an impact on the patient reader. John Donne takes full advantage of the “chaos of violent and transitory passions” that should have limited him and turned them into iconic lines that change any who read them (Lewis 121).

Works Cited

Donne, John. “Elegy XIX” and “The Flea.” The Complete Poetry and Selected Prose of John Donne. Ed. Charles M. Coffin. New York: Modern Library, 2001. 31, 85.

Greer, Germaine. “Donne’s ‘Nineteenth Elegy.’” A Companion to English Renaissance Literature and Culture (Blackwell Companions to Literature and Culture). Ed. Michael Hattaway. Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishers Ltd, 2003. 215-223.

Jackson, Robert S. John Donne’s Christian Vocation. Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 1970. 5.

Lewis, C. S. “Donne and Love Poetry in the Seventeenth Century.” Selected Literary Essays. Ed. Walter Hooper. London: Cambridge University Press, 1969. 106-125.