I discovered recently that a couple of my previous essays, ones that had not been polished but made it out into the interwebs anyways, have been cited by people in their academic work. That gave me pause, since they were still in very rough form. I’ve decided to ensure a better edited version of this work is on the World Wide Web, in the event it ever comes up again. There will be two more of these updated essays, one in July and one in August.

When thinking about the four different Gospels found in the New Testament, every reader easily notices the different accounts of Jesus’ life. Of the Gospels, the three Synoptic Gospels present a unique problem for scholars and academics. Matthew, Mark, and Luke, when looked at together, give us a singular picture of Jesus and His ministry. Differences are abundant, but the overarching tapestry of Jesus’ life is presented in strikingly similar accounts. While John’s Gospel takes on a form and shape of its own, the other three take on a singular shape, written down in slightly differing versions. What could cause such a resemblance? Perhaps the authors relied upon each other? Or instead, maybe they used a common source that isn’t in the New Testament because it was lost or destroyed? Could the similarities be traces of an oral tradition that communicated the story of Jesus? These are the questions that make up the Synoptic Problem.

Scholars have attempted to solve the riddle of the Gospels since the time of the early Church Fathers. Clement of Alexandria and Augustine of Hippo were two of the earliest scholars to produce theories explaining the sequence of the Gospels, asserting that the similarities between the three Synoptic Gospels stemmed from one author relying upon a previous one (Goodacre, 76). Interestingly enough, the idea that the three Gospels relied upon one another was considered a sufficient theory for several hundred years. The Two Gospel theory took on different appearances as Biblical criticism grew during the Enlightenment. Some claimed Matthew wrote his account first, and Luke used Matthew’s Gospel to write his own, while Mark used both previous Gospels to pen his own. Others asserted Markan priority, which meant that Matthew could have written his Gospel next, and Luke could have used the two Gospels already written in his research (Goodacre, 56-57; Luke 1:1-4). While still claiming Markan priority, the reversal of Matthew and Luke could also be assumed to create another variation on the Two Gospel Theory. While these variants bore resemblances to the ancient theories put forth by the Church Fathers, a new theory arose in the mid-Eighteenth century that added a new dimension to the debate.

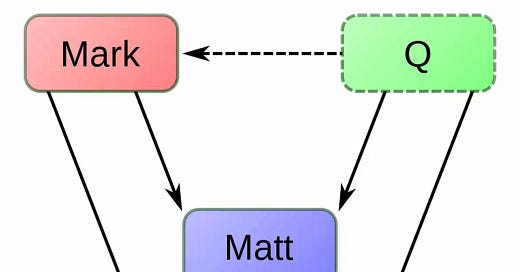

The idea that another document existed that told the story of Jesus began to gain momentum among academics after the idea was put forth. While first merely a suggestion, theories claiming that the writers of the Gospels had used another source that predated the earliest New Testament Gospel exploded onto the scholarly scene over the course of the next two hundred years (Goodacre, 21). While many theories have arisen, the two most prominent theories are the Two Gospel Hypothesis and the Q Hypothesis. As stated earlier, there are differing opinions of exactly how the Two Gospel Hypothesis plays out between the three Synoptic Gospels, but the most widely accepted version asserts that Mark was written first (from here on referred to as Markan Priority). The Q Hypothesis is also filled with multiple concepts and claims, but the overall idea is that the earlier Gospel used by the New Testament authors is referred to as Q. As a hypothetical document, no physical evidence of Q has ever been found. “The existence of Q was suggested because of the presence in Matthew and Luke of very similar material not contained in Mark . . . If the document Q existed, it likely would have been a collection of Jesus’ sayings with little narrative content” (Lea and Black, 121). Q presented a seeming solution to the Synoptic Problem, providing an alternative source rather than relying on the Biblical text alone.

The issue at the root of the various theories concerning source criticism is the belief that the Gospels could not have so many things in common without needing an outside source. The Synoptic Problem can be summarized in three main points (Lea and Black, 114):

Since the authors of the New Testament Gospels all follow the same main timeline, beginning with Jesus’ baptism and ending with His Passion and resurrection.

The three Gospels all have sections of verbal communication that are strikingly similar, while at times two Gospels have more in common than the third, which suggests that the Gospels must have been composed at separate times.

The Gospels have surprising number of grammatical differences despite their obvious commonality, particularly in the word choice during Christ’s Passion.

All these differences, when taken together, would suggest that some kind of interdependence exists, yet that would not explain the differences within the texts. And that is where the Q Hypothesis steps in to provide an answer. Of course, these differences need not be explained away. If scholars examined them as individual works, a suitable solution might present itself. Daniel Wallace explained it best:

Each biblical writer wrote the very words of God, yet each exercised his own personality and will in the process. The message originated with God, yet the process involved human volition. The miracle of inspiration, as Lewis Sperry Chafer long ago noted, is that God did not violate anyone’s personality, yet what was written was exactly what he wanted to say.

Looking at the Gospels as independent works that borrowed from and used each other’s work is not a far-fetched concept. It is an underrated idea but is certainly not something to be treated as alien or impossible. When an individual read the Gospels in the New Testament, it is important to note that a different author wrote each Gospel. And each author had a unique purpose in presenting the story of Jesus Christ.

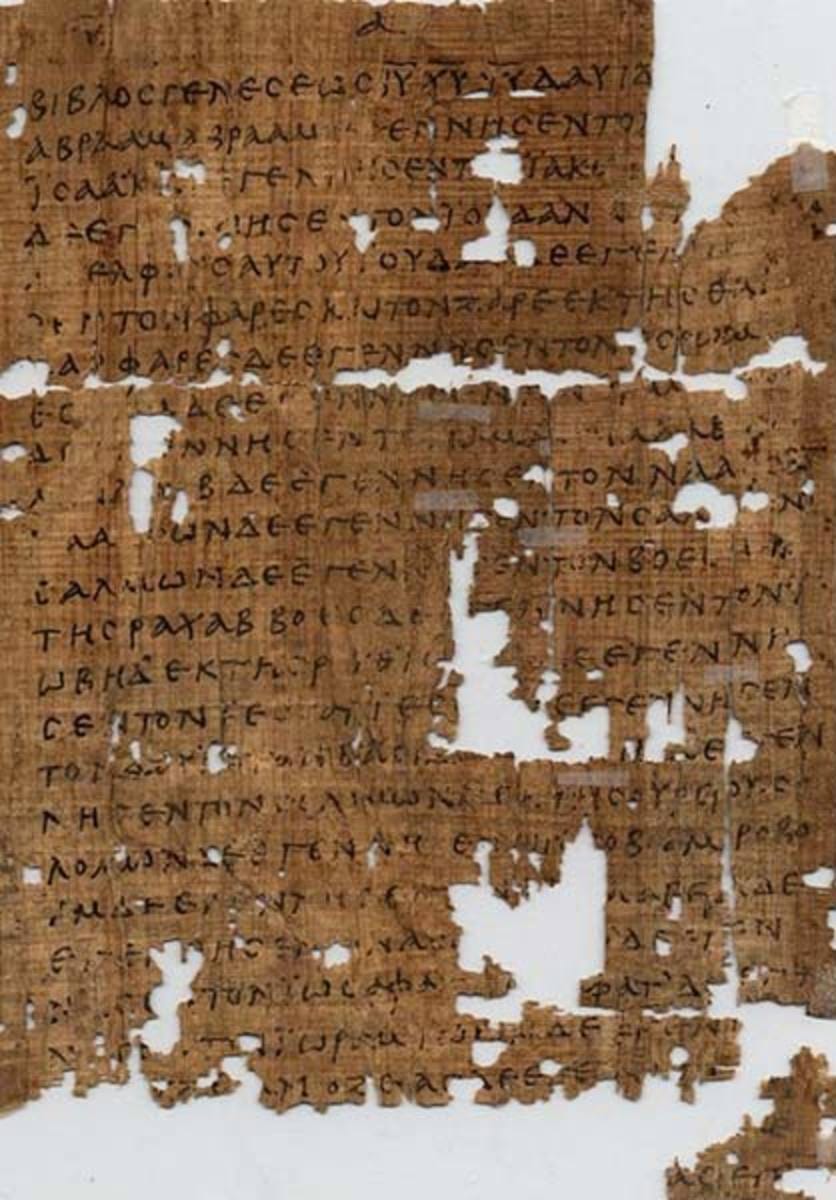

From the very outset of the Gospels, the differences and similarities can be seen. For instance, Matthew and Luke both begin their Christ’s genealogy (although their genealogies are not the same), while Mark begins with the preaching of John the Baptist and the Gospel of John opens with a reference to the book of Genesis. Matthew and John also include portions of Jesus’ childhood in the beginning of their Gospels, while the Gospels of Mark and John take up with Jesus as an adult. The differing elements often hint at the purpose of the author and where their emphasis was focused.

Matthew, with his Abrahamic genealogy that showed Jesus as a descendant of Solomon through his earthly father Joseph, might have had a mostly Jewish audience in mind when he was writing (Lea and Black, 137) His inclusion of the birth of Christ and the events that led to Jesus’ eventual settlement in Nazareth are designed to show how Jesus was the Messiah because He fulfilled the ancient prophecies. Luke, by contrast, begins with an Adamic genealogy that traces Christ back to the original man, but not through Solomon. Instead, Luke follows the lineage of Seth through Jesus’ mother Mary, thus avoiding the cursed line of Solomon while also broadening Jesus’ family tree (Jeremiah 22:24-30) By including Jesus’ ancestors beyond Abraham, Luke is appealing to both a Jewish audience and a Gentile one. Jesus fulfills prophecy by being of the proper household, and He is also connected to all mankind. Mark’s Gospel begins with a brief introduction to Jesus through prophecy and then cuts straight into the ministry of John the Baptist. Mark’s focus seems to be more on the actions of Jesus than anything else. His beginning sets up the pattern he would use throughout the Gospel to concentrate on what Jesus did as opposed to ancient prophecies and Jesus’ words (Lea and Black, 143). And the Gospel of John, taking a unique approach, begins by first establishing Jesus as the Word of God who “was in the beginning with God” (John 1:2). By starting with establishing Jesus’ identity as the Messiah, John may have been aimed at a Jewish audience (Lea and Black, 163). But regardless of whomever the Gospel was written for, it was clearly written to bring people to salvation at the feet of Jesus (John 20:31).

Examining the similar beginnings of Matthew and Luke more closely, several questions arise. Why do the two Gospels portray different elements of Jesus’ childhood? One reason may be found in Luke’s declaration that he “investigated everything carefully from the beginning,” and as such he included the details he gleaned about Jesus at an early age (Luke 1:3). Luke uses prophecies and visions and angels to all demonstrate the supernatural beginning of Jesus’ life. Luke makes it clear that the birth of Jesus had been foretold as according to God’s plan, and that everything had been fulfilled just as God said it would. Matthew’s telling of Jesus’ birth doesn’t have quite the elaborate “foretelling” that Luke does. Matthew uses dreams to explain the knowledge that Joseph and Mary receive concerning Jesus, and Matthew’s concentrated “prophecy fulfillment” supports the notion that he was primarily writing to Jews who would have been looking for certain scriptures to be fulfilled.

Although the two lineages of Jesus found in Matthew and Luke seem to present a problem, in truth the differences can be reconciled. It makes sense that the two lineages are those of Joseph (Matthew) and Mary (Luke). Although the text in Luke never says it is Mary’s lineage, it would logically follow that Luke would not have gotten a different lineage through interviews. As Luke, and Matthew, both insist Jesus had not earthly father (Matthew 1:8, Luke 1:35). But Matthew, following the Jewish tradition, listed the genealogy of Jesus through Joseph (Essential Guide, 14-15) Perhaps relying on an Old Testament example found in Numbers 26-27, Luke was attributing a pure line of ancestors of Christ through Mary since Joseph was descended of the cursed line of Jeconiah (Essential Guide, 189). This gives serious credibility to the idea that the separate genealogies are not in conflict, but instead are complimentary to one another

There are attractive features to the theories that build upon a mysterious ‘extra’ gospel. Yet, as enticing as those theories may be, much is lacking in the way of evidence to support them. “But since ‘Q’ owes its existence completely to the conclusions drawn from a hypothetical model, such an argument flies in the face of logic: it annuls its own basis” (Klinghardt, 3). As Q is a fabricated document, borne from the minds of scholars who saw problems in the Gospels, it cannot be treated as a solid ground to stand on. While it is true that the “plausibility of a hypothesis is dependent in part on the implausibility of its main alternatives,” that does not give a hypothesis evidence nor proof for “Q is premised on the unlikelihood that either of the later evangelists is dependent on the other in addition to Mark,” yet there is no reason to build upon such a premise (Watson, 398). Considering that Markan Priority does not pose critical issues in the same manner as the Q Hypothesis simply because there is physical evidence of Mark, and none of Q (Klinghardt, 3). Why, when there is evidence that connects the Gospels, would an invented document take priority? Is the reason because the Two Gospel Hypothesis does not answer the Synoptic Problem sufficiently? Possibly.

To take such a stance is unnecessary, however. In his essay, “On Dispensing with Q,” A. M. Farrer goes to great lengths to examine the multitude of reasons that the Q Hypothesis carries little weight, and he reconciles many of the issues that plague academics who see too many issues within the New Testament Gospels to rely on the Two Gospel Hypothesis. Farrer’s work is lengthy, and thorough, and certainly deserves more space than can be provided for them here. In summary of his work, he writes:

The surrender of the Q hypothesis will not only clarify the exposition of St. Luke, it will free the interpretation of St. Matthew from the contradiction into which it has fallen. For on the one hand the exposition of St. Matthew sees that Gospel as a living growth, and on the other as an artificial mosaic, and the two pictures cannot be reconciled. If we compare St. Matthew with St. Mark alone, everything can be seen to happen as though St. Matthew, standing in the stream of a living oral tradition, were freely reshaping and enlarging his predecessor under those influences, practical, doctrinal and liturgical, which Dr. Kilpatrick has so admirably set before us in his book [G. D. Kilpatrick, The Gospel According to St. Matthew (Oxford: Clarendon, 1946)]. But then the supposed necessity of the Q hypothesis comes in to confuse us—these apparently free remodellings of St. Mark cannot after all be what they seem, nor are they the work of St. Matthew in his reflection on St. Mark, for they stood in Q before St. Matthew wrote. And that is not the end of the trouble, for if the so-called Q passages were in a written source, so, we must suppose, were other Matthean paragraphs which have the same firmness of outline as the Q passages and are handled by the evangelist in the same way. They were not in Q, or St. Luke would have shown a knowledge of them, which he does not do. Never mind, we can pick another letter from the alphabet: if these are not Q passages, let them be M passages, or what you will. Once rid of Q, we are rid of a progeny of nameless chimaeras, and free to let St. Matthew write as he is moved. (85)

His frustration with the Q Hypothesis is clearly seen and is warranted to a certain degree. Farrer’s most cogent point regards the views concerning Matthew and Luke, which still stands as the root of the problem with the Q Hypothesis. There is no need to rely on an outside source, if the perspectives in the inside sources are not focused on treating only suspicions and ideas of inferiority.

What does it mean to solve the Synoptic Problem? The discovery of another Gospel that could be identified as Q is on solution. But, in the end, that would probably lead to more questions. Another solution could be to cling to Markan Priority and attempt to connect the dots between the Synoptic Gospels to form a harmony between them. That is the solution that answers questions rather than raise new ones. And even then, not all answers can be fully examined. The grammatical and syntactical arguments that exist in the debate about the Gospels will never find a solution in either hypothesis, since much of those arguments are premised on the idea that something is wrong when scholars try and compare the Gospels. Understanding that the Gospels serve as complements to each other, a purpose that may very well have been done on purpose if Matthew and Luke felt so inclined, will bring to light a fresh view on the Scriptures. The conclusion of Dr. Wallace is echoed here: “I am persuaded that the closer we look, the better the Bible looks. Or, as an old British scholar of yesteryear said, ‘We treat the Bible like any other book to show that it is not like any other book.’”

Works Cited

Essential Guide to the Genealogy of Christ. Peabody, MA: Rose Publishing, 2021.

Farrer, A. M. “On Dispensing With Q.” In Studies in the Gospels: Essays in Memory of R. H. Lightfoot. Edited by D. E. Nineham. Oxford: Blackwell, 1957. 55-88.

Goodacre, Mark. The Synoptic Problem: A Way Through the Maze. London: Continuum, 2001.

Klinghardt, Matthias. “The Marcionite Gospel and the Synoptic Problem: A New Suggestion.” Novum Testamentum 50 (2008): 1-27.

Lea, Thomas D., and David Alan Black. The New Testament: Its Background and Message. Nashville: Broadman & Holman Publishers, 2003.

Wallace, Daniel B. The Synoptic Problem and Inspiration: A Response. 2000. http://bible.org/article/synoptic-problem-and-inspiration-response.

Watson, Francis. “Q as Hypothesis: A Study in Methodology.” New Testament Studies 55 (2009): 397-415.