This is Humanism

A Reflective Journey Towards a Definition

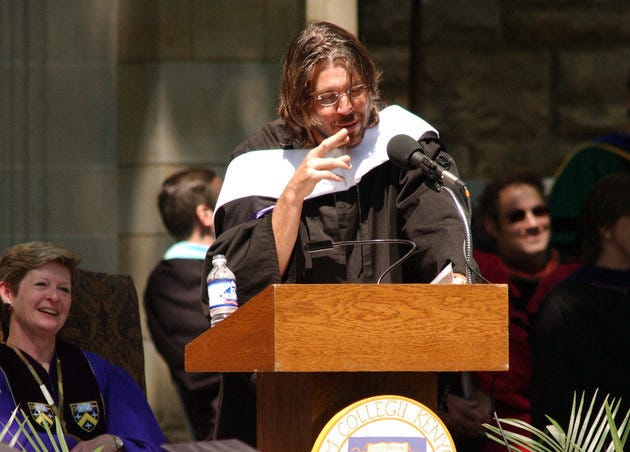

At a 2005 graduation ceremony, David Foster Wallace opened his commencement speech with a joke: “There are these two young fish swimming along and they happen to meet an older fish swimming the other way, who nods at them and says ‘Morning, boys. How’s the water?’ And the two young fish swim on for a bit, and then eventually one of them looks over at the other and goes ‘What the hell is water?’” After eliciting the expected, but not enthusiastic chuckles, Wallace went on to explain that his lead in was more than a humorous story: “The point of the fish story is merely that the most obvious, important realities are often the ones that are hardest to see and talk about” (“This is Water”). For all the talk of rights and culture prevalent in the world today, the most important reality that many seem to miss is a quite simple one: what does it mean to be human? It is a core question that spans thousands of years, millions of books, and billions of minds. Its answer might not be 42, but it is indeed the question. But as many have pointed out throughout humanity’s tenure on this planet, the question itself is part of the answer. As Mortimer Adler pointed out, “the ultimate questions which man asks about himself are partly answered by the very fact of their being asked” (11). Human beings understand who they are by asking questions about existence. And it is also true that individuals often forget their humanity, for it is one of those “obvious, important realities” that prove difficult to discuss and understand.

For many years in my own mind, Humanism and Atheism functioned as equivalents. I could not have told you where that idea originated precisely, since I did not encounter the Humanist Manifestos until after I had begun graduate studies. Still, the concept appeared to me as some intellectual attempt to make mankind the center of the universe, effectively replacing the Divine. Perhaps this is the remnant of my public high school history lessons, which sought to boil the Enlightenment down to a few testable concepts. After I began studying Church History, I encountered Erasmus and from there my understanding of Humanism began to take on real shape. It is not that Erasmus makes understanding his views easy; what does one make of the theologian who writes, “the whole of human life is nothing but a sport of folly” (11). But his influence on Luther and the subsequent Protestant Reformation set me to thinking that Humanism, at least of the Christian variety, must be something that seeks to understand humanity’s role in the cosmos, instead of attempting to replace God at the center.

I began, then, with the idea that Humanism holds that there is something unique about mankind, something which makes the study and discussion of man take on a more significant meaning than the discussion of other living creatures. It is a philosophy primarily concerned with the soul: “With an immortal soul, man belongs to eternity as well as to time. He is not merely a transient character in the universe. His stature and his dignity are not the same when man regards himself as completely dissolvable into dust” (Adler, 9). This branch of study, an anti-empirical anthropology, asks why we make music while also providing a context for judging said music in the larger scheme of humanity’s story. Humanism ought to be an approach to understanding humanity, while placing him in his proper context; namely, mankind is a metaphysical creature inhabiting a physical world, building towns, and creating artwork which will one day pass away just as the flesh does.

Russell Kirk, who helped further hone my concept of humanism, draws upon Irving Babbitt to insist that “humanism . . . is an ethical discipline, intended to develop the truly human person, the qualities of manliness, through the study of great books” (162). Humanism is understood in this light as the pursuit of knowledge, primarily derived from the cultural legacy of the past. What is the purpose of humanity? What does it mean that man discusses? Is there more to culture than the shifting views of the moment? Humanism may not answer all these questions, but it does provide an undergirding framework for individuals to explore such queries. For Humanism posits that such questions can be answered, and more, that such questions ought to be answered. And for the Humanist, the answer is found when the past is brought to bear on the present. Individuals and communities learn to be more fully themselves, through understanding what is meant by the term “human being.” Humans are in a way that no other creature can be said to be.

Or, to return to Wallace’s story, Humanism is the attempt to grasp those realities which the individual is constantly steeped in but can’t quite put their finger upon. It But Humanism does not dismiss the passing elements of the world; it is only by art and culture that man begins to understand his context. This idea of context is vital in getting a firm grasp on Humanism, for the squishy nature of definitions quickly derails attempts to do so. Irving Babbitt helpfully separates Humanism from humanitarianism, the latter represented by those who “has sympathy for mankind in the lump, faith in its future progress, and desire to serve the great cause of this progress,” who “stress almost solely upon breadth of knowledge and sympathy” without so much as word on judgment or discernment (7). Babbitt provides the tools that Humanism needs to be more than vague abstractions, though he is also careful to avoid concretizing too much. Like Solon before him, Babbitt seems aware of the dangerous nature in strict codification. As Babbitt explains it, Humanism “is interested in the perfecting of the individual,” maintaining a “just balance between sympathy and selection,” (8-9). To do so, man needs three things: a tradition in which he may find himself a part, a willingness to discipline his passions, and appreciation for the standards which exist outside of the individual. Each of these works together to help the Humanist grasp a moderation necessary for the social extremes surrounding him at every turn. Humanism does not offer an empirical answer to the question, “what does it mean to be human?” But it does provide a guide to recognizing the plain reality, the water in which individuals swim each and every day.

Wallace concludes his speech by returning to his fish story and encouraging the college graduates that morning to adopt an “awareness of what is so real and essential, so hidden in plain sight all around us, all the time, that we must keep reminding ourselves over and over: ‘This is water.’ ‘This is water.’” Humanism likewise is of a kind which needs constant revisiting. The core elements of what it means to be a human never change, but its outworkings remain anchored to a specific time and place which must not be forgotten. The Humanist, aiming for moderation, is constantly aware that everyone is asking the question, and that the answer may present itself in varying, subtle ways. But the Humanist also knows that the traditions, the standards that serve as his guiding lights, mean that the core of every response remains the same. “Whatever answer is given, man’s asking what sort of thing he is, whence he comes, and whether he is destined symbolizes the two strains in human nature—man’s knowledge and his ignorance, man’s greatness and his misery” (Adler, 11). Humanism is the attempt to ennoble the individual, without resorting to coercive means, so that his greatness might mediate his misery, so that his knowledge might have a fighting chance to balance out his ignorance. In the end, it is reasonable to paraphrase Wallace’s speech one final time: This is Humanism. This is Humanism.

Bibliography

Adler, Mortimer J., ed. “Man.” In The Syntopicon: An Index to the Great Ideas. Second Edition. Vol. 2. Great Books of the Western World. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 1990. 9-27.

Babbitt, Irving. Literature and the American College. Boston, MA: Houghton, Mifflin, and Company, 1908.

Erasmus, Desiderius. The Praise of Folly. In Praise of Folly; The Essays. Edited by Mortimer J. Adler and Philip W. Goetz, Translated by Betty Radice, Second Edition. Vol. 23. Great Books of the Western World. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 1990. Vii-42.

Kirk, Russell. “The Moral Imagination.” In The Essential Russell Kirk: Selected Essays. Edited by George A. Panchias. Wilmington, DE: ISI Books. 159-167.

Wallace, David Foster. “This is Water.” Commencement Address given at the 2005 Kenyon College Graduation, Gambler, OH, May 21, 2005. https://web.archive.org/web/2008 0213082423/http://www.marginalia.org/dfw_kenyon_commencement.html.

Splendid post, Sean. I’m just finishing Babbitt’s ‘Democracy and Leadership.’