You Know There'll Be Trouble

ASK Recommends: High Noon (1952)

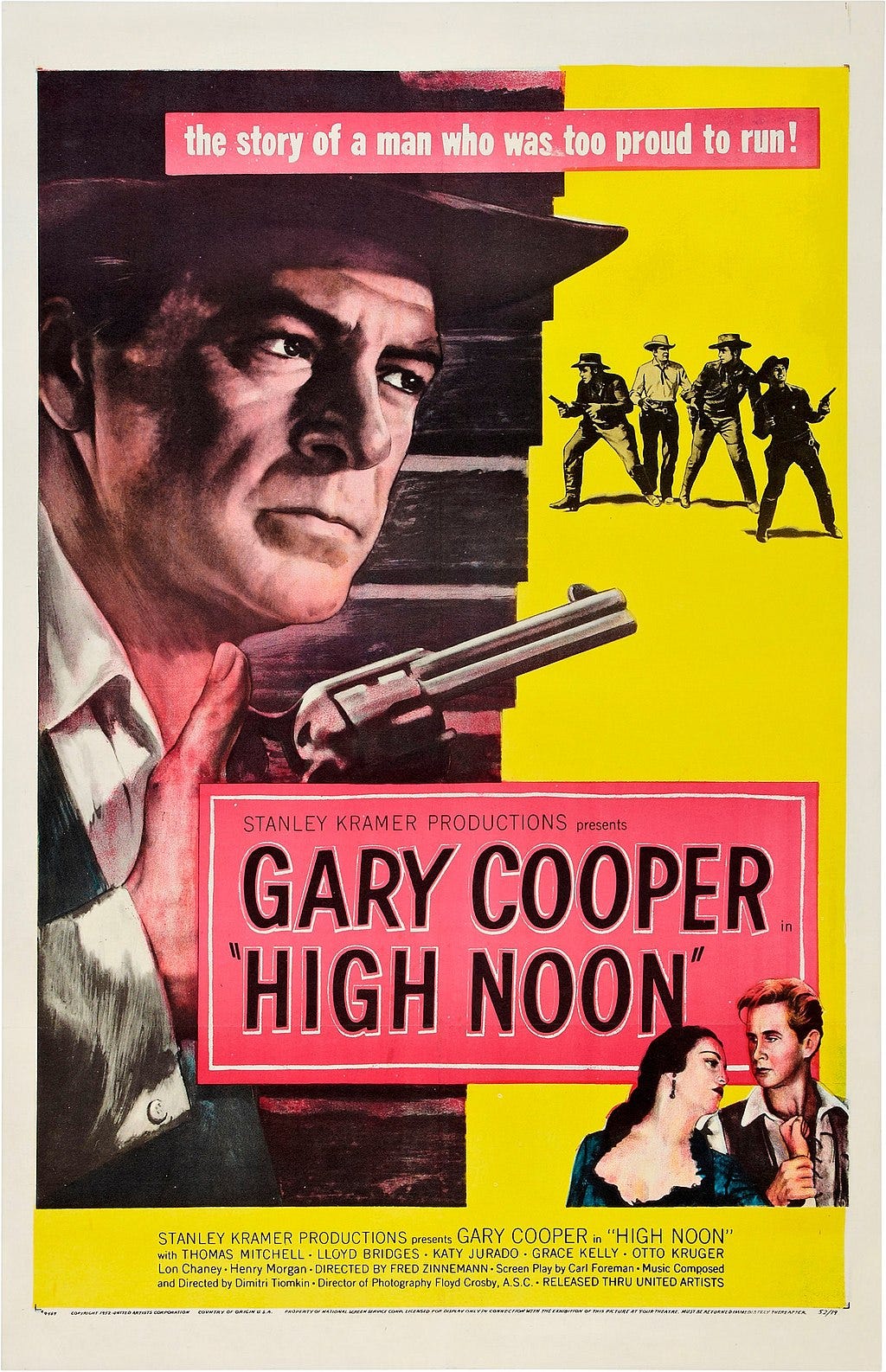

High Noon. Directed by Fred Zinnemann, featuring Gary Cooper, Thomas Mitchell, Lloyd Bridges, Katy Jurado, Grace Kelly, Otto Kruger, Lon Chaney, Henry Morgan, and Lee Van Cleef. United Artists, 1952.

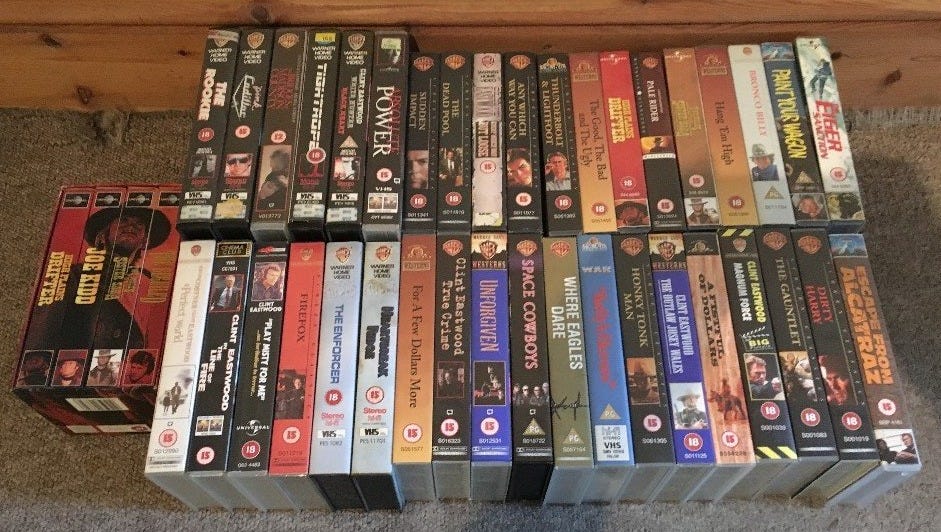

I have a soft spot for Westerns. Some of it stems from the sheer number of them I watched growing up. We owned the entire Clint Eastwood collection on VHS. In college, I lived briefly with my grandparents, and they loved Westerns. As a freshman, one of my favorite Friday night events was watching a Western on AMC with my grandfather, something he’d seen a dozen times before but was typically new to me. So I’ve seen a lot of these movies over the years.

But High Noon is a movie I’ve only ever seen twice. No reason in particular, other than the happenstance of time and place. I don’t know if this means it wasn’t popular enough in the Early Aughts to warrant repetition on Cable Television, but I would not be surprised if that’s the case. The movie is fundamentally about the objective nature of right and wrong, something that many of my college peers rejected outright. There are many nuances to the film, but this singular idea is not one of them. As you follow the marshal, Kane, to the final confrontation, there is never any doubt left for the viewer that he is doing what is right. You can disagree with his decision to do the right thing, but the movie doesn’t leave you any room to say he is doing the wrong thing.

You’d be forgiven for making much ado about how few political references there appear to be in a movie called one of the greatest political films of all time. Of course, some of the political intonations stem from the historical context of the movie, filmed during the height of the Red Scare and McCarthyism. Add to that John Wayne’s initial refusal to support the film and then his subsequent Oscar’s speech on Cooper’s behalf, and the whole thing has enough steam to be a story on it’s own.

While the backstory holds a certain fascination, I think this is a movie that stands on its own in a number of ways. I want to run through just a couple of them, offering these examples as reasons for you to watch the film yourself. Then you can judge whether I’m on the right track.

First, the casting of the older Gary Cooper opposite the younger Grace Kelly is perfect. Since so much of the film is focused on the more-and-more haggard visage of Cooper’s Kane, his young wife serves as a reminder of his vitality. Cooper refused make-up for the film to make him look younger, in a large part of emphasize the burden his character bears. This works by itself, but by pairing Kane with a young effervescent wife, the contrast is highlighted even further. The burden of doing the right thing wears a man beyond his years, and this is made visible throughout the film.

Second, the presence of children throughout the film is so meticulously placed that it creates a strong visual element that hits the right emotional notes. I’ve written elsewhere about the importance of rightly understanding Aristotle’s Spectacle for visual adaptations, and the Western is a place where gun fights and fisticuffs can often replace nuanced storytelling. But the director Zinnemann clearly has an eye for detail. The church scene is really key here. After the adults excuse the kids from the room, suggesting that the adults need to have a frank discussion, Kane exits pretty quickly. But what does the camera catch as he leaves? The children playing tug-of-war just next to the church steps. Kane walks by, and the kids all fall down, with no one winning. The children play other important roles, whether invoked as a reason to support Kane, or as emotional foils playing games in the empty streets where courageous parents ought to be gathering, and every time the viewer is left to reflect on the cowardice and indecision of the townsfolk.

There are more reasons to watch the film, of course, but I’d rather not discuss all the details which make the movie great. There’s Lloyd Bridges as a young hothead in an outstanding role. Great dialogue pops up throughout, never too on the nose but never avoiding the plain right-and-wrong tension which undergirds the story. And the menacing countenance of Lee Van Cleef, along with his harmonica, creates one of the best speechless movie villains I can recall.

Ultimately, I would wager that this film is 82 minutes that you won’t regret.