When I first started considering graduate school in 2008, there was a strong push for me to rethink my course. “There are too many English PhDs out there already. The chances of you getting a professorship are simply too slim at the current rates.” It was an alarming idea, that I could devote my life to study and then find myself “unemployable” as a result. The fear that the English market was oversaturated was palpable and on display everywhere in the department. Having finally completed my own PhD in Literature, and thinking about the future, now seemed an apt moment to see what the landscape looks like.

I first really began to think about this a few years ago when I read English Literature by David Daiches. Daiches argued in 1964 that a PhD was not really necessary to equip a university English teacher, but that the doctoral program ought to be focused on literature rather than training new professors. I think the Scotsman was on to something, even more in 2024 than in 2017.

And looking at the numbers can shed some light on the argument. 57,596 doctorate degrees were earned in 2022, an uptick from 52,194 in 2021.1 Of those, Humanities degrees accounted for 6%, and Literature only 3%.

When looked at in individual categories, English and Literature certainly make up the largest group within the Humanities category. Humanities PhDs numbered 3,369 in total, while English and Literature PhDs numbered 1,600, or 47% of that group. There are two groupings, English Language and Foreign Language, which have a lot of overlap broadly speaking but and more tailored when closely examined.

The Foreign language category in the survey is rather broad and would not include much of my own area of expertise. So, narrowing down specifically to the English Language and Literature category helps unpack concentrations are dominant in the field and gives a better idea of how things look.

The 7% labeled as “nec” means Not Elsewhere Classified. But only 138 doctoral graduates concentrated on American Literature in 2022. Since that was my area of focus, I’m curious who these folks are and what they’re doing now. And while I don’t see a whole lot of job postings focused on American Literature, this doesn’t strike me as a dire situation. Competitive? Yes. But not insurmountable.

I wondered if it might be helpful to think about this question by comparing English PhDs with another category, so I chose one that had steady growth since 1985 and in 2022 was roughly even with the “Non-Sciences” category as a whole: Engineering. Out of all the PhDs awarded in 2022, 20% overall were earned in this non-Science field total. Comparatively, out of all PhDs awarded in the same period, 19% were in Engineering fields. This is interesting since there is a stated shortage of engineers in the labor market.2

Engineering PhDs tend to be younger than those graduates from the Humanities fields. 59% of Engineering PhDs are earned before the graduate is 30 years old, and there is a steep decline after the age of 30. By contrast only 21% of Humanities PhDs are earned before the age of 30, and the drop off does not begin until after 35. But even here, the drop off is nowhere near as steep and there is actually a slight increase of Humanities PhDs from the 41-45 to Over 45 categories.

How does this compare with wider trends?

The estimated population in the United States in 1985, America’s population was around 235,146,181. 3,166 of them earned an Engineering doctorate and 435 earned a PhD in English (0.0013 and 0.00018 of the total population, respectively). By contrast, in 2022 was 334,914,895. 335 million people and 1,062 such citizens earned an English PhD (with only 138 of them studying American Literature). Meanwhile, 10,763 graduated with a PhD in Engineering.

Since 1985, the growth rate of PhDs in the Humanities has remained fairly steady, while the numbers of Engineering PhDs have continued to climb.3 When the numbers are isolated to look at English PhDs specifically, the relative stability of English programs seems evident, and the growth of Engineering degrees becomes a bit starker.4

So, are there too many English PhDs? It depends.

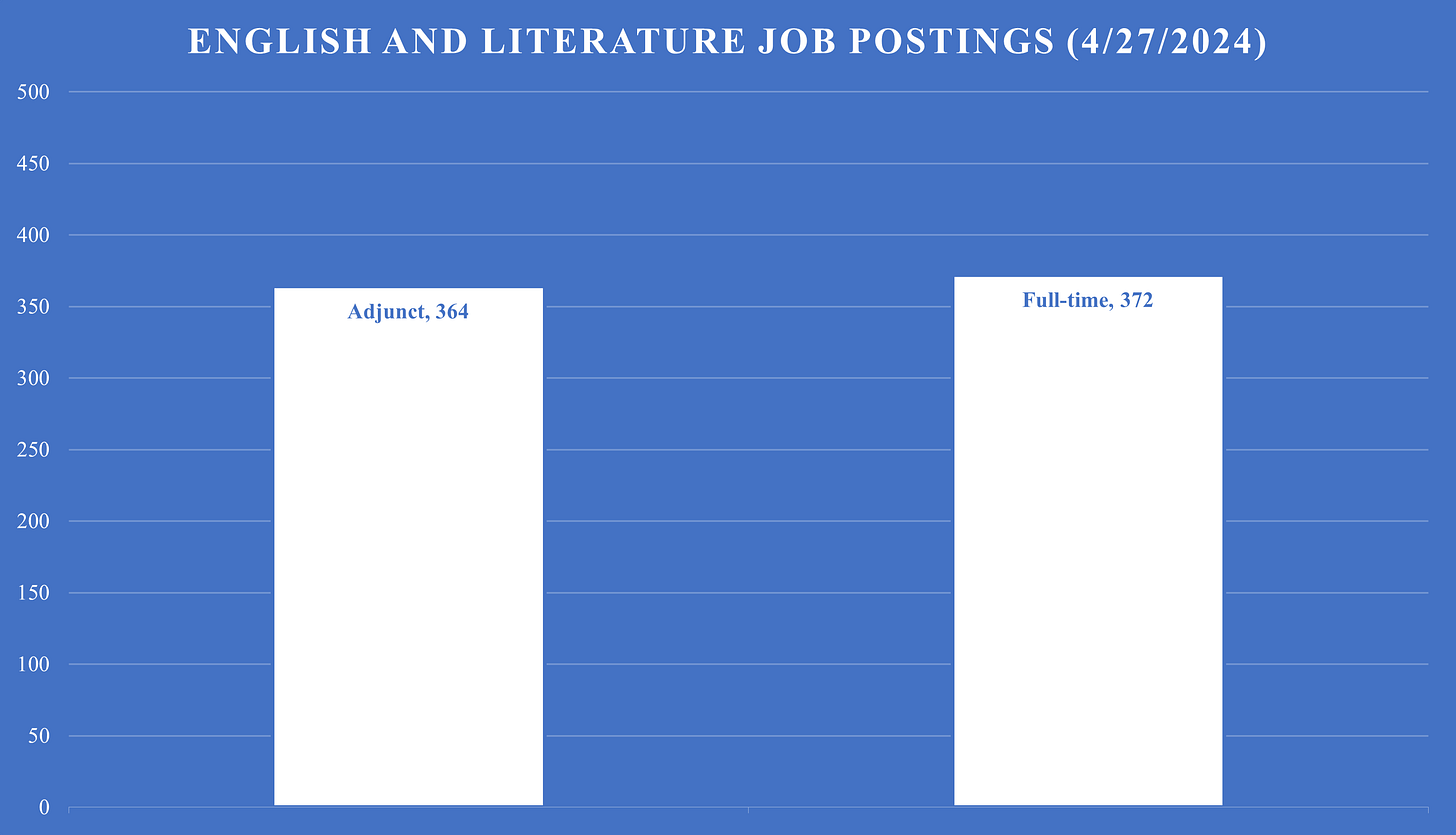

If you’re thinking in terms of PhD-to-College-Professor job training, then you’re probably in the same camp as Kevin Carey. He was decrying the overproduction of PhDs in 2020, right as the COVID shutdowns started changing the higher ed lanscape.5 As of April 27th, HigherEdJobs listed 736 postings for the category of English and Literature as active since September 1, 2023.6 Almost half of those are for adjunct positions (49%) and the rest are for full-time spots (51%). Some of these postings may be mistakes (more than one History listing was cross posted here, something worth looking into on its own). So, if every full-time job was filled by a newly minted PhD, there would still be 690 graduates looking for work. And if each of them took up one adjunct position, there would be 326 left without any academic options (roughly one-third).

Except that this is far from what happens. Some of those who graduate with a PhD in English are already employed as professors because they have a Master’s degree that gets them in the door. Also, quite a few of these postings on HigherEdJobs will be filled internally. Add to that the movement of scholars from one institution to another, and it becomes virtually impossible to know who will get what jobs.

Curiously, in 1980, there were 3,231 accredited colleges in the United States. In 2021, there were 3,931.7 Even with all the talk of closing colleges, there are more four-year degree granting institutions today than there were 40 years ago. An increase in English PhDs to teach at colleges appears to be a necessity on the sheer growth of colleges over that period. The increase in Engineering PhDs, from 3,166 to 10,763 would suggest an overcrowding, if Engineering PhDs were told that all they were meant to do was teach college classes.

And I would wager that therein lies the problem: is it true that the only real profession for someone with an English PhD must be teaching in the college classroom? I can’t imagine that advisors are saying such things to engineering students. And while yes, I recognize the technical skills involved in the latter, there is plenty of evidence that Engineering PhDs don’t all go into their immediate field. Sometimes, people study a thing and take that learning elsewhere. And, wildly enough, they have success. I hope to write more about the problem of specialization in the future, but for now, I will simply say this: I don’t think there are too many English PhDs. I think, if anything, there are too many career advisors and HR people who think a person is only as capable as what they studied.

This is an area that I think the Classical Education movement can overcome, both in rethinking the purpose of education and by building institutions more in line with the older model of education. Add to that the growing number of alternative programs,8 which invite adults to think of learning as something more than mere job training, testifies that there is indeed a felt need for a better understanding of what it means to learn.

All data comes from the National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics. 2023. Doctorate Recipients from U.S. Universities: 2022. NSF 24-300. Alexandria, VA: National Science Foundation. Available at https://ncses.nsf.gov/pubs/nsf24300.

Cf. Jay Landers, “A Boost for Infrastructure,” Civil Engineering, January/February 2022, https://www.asce.org/publications-and-news/civil-engineering-source/civil-engineering-magazine/issues/magazine-issue/article/2022/01/2022-the-first-of-several-solid-years-for-the-aec-industry.

Kevin Carey, “The Bleak Job Landscape of Adjunctopia for Ph.D.s,” The New York Times, March 5, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/05/upshot/academic-job-crisis-phd.html.

These comparisons over time use the National Science Foundation, National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics. 2017. Doctorate Recipients from U.S. Universities: 2015. Special Report NSF 17-306. Arlington, VA. Available at https://www.nsf.gov/statistics/sed/2017/nsf17306/.

The categories under “Engineering” and “English” changed from 2015 report to the 2022 report. But even accounting for those changes, there remains less growth in the “Literature and Languages” categories compared with the “Engineering” group.

I went in and manually counted to avoid inactive postings that are still posted, https://www.higheredjobs.com/faculty/.

National Center for Education Statistics. (2022) Table 105.50. Number of educational institutions, by level and control of institution: 2010–11 through 2020–21 [Data table]. In Digest of education statistics. U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences. Retrieved November 15, 2022, from https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d22/tables/dt22_105.50.asp.

This piece details a few such programs:

Depressing trends. It doesn't make the PHD worth less (in fact, I think having a PHD is a good, in and of itself), but it definitely raises the question about academia and its legitimacy.