Batman & Aristotle, Pt. 2

When Poetics and Aesthetics Collide

This is the second part of my essay on Batman and classical aesthetics. The first part can be read here:

Batman & Aristotle, Pt. 1

Are comic books art? Starting with the most basic conception of the question, the answer is obviously yes. Materials. Skill. Creativity. All of these are required for the creation of a comic book. Are comic books good art? Now, that is a different question. People have answered the question differently, often coinciding with how they interacted with com…

Batman, in the Aristotelian sense previously defined, is the most moral of the superheroes. His stories capture the dichotomy set out by Aristotle, bringing katharsis and mimesis out of the Greek Amphitheatre and placing them on the leaves we hold in our hands. A brief analysis of two distinct story arcs, which hit shelves at roughly the same time, will serve to illustrate what is meant by this claim. Jeph Loeb and Jim Lee’s Hush story stands as the premier tragic tale from the early 2000’s, while Frank Miller’s anticipated sequel, The Dark Knight Strikes Again, embodies the comic genre through the medium of the comic book. These two stories contain striking similarities in terms of layout and storyline, which makes them an appropriate venue for analysis.

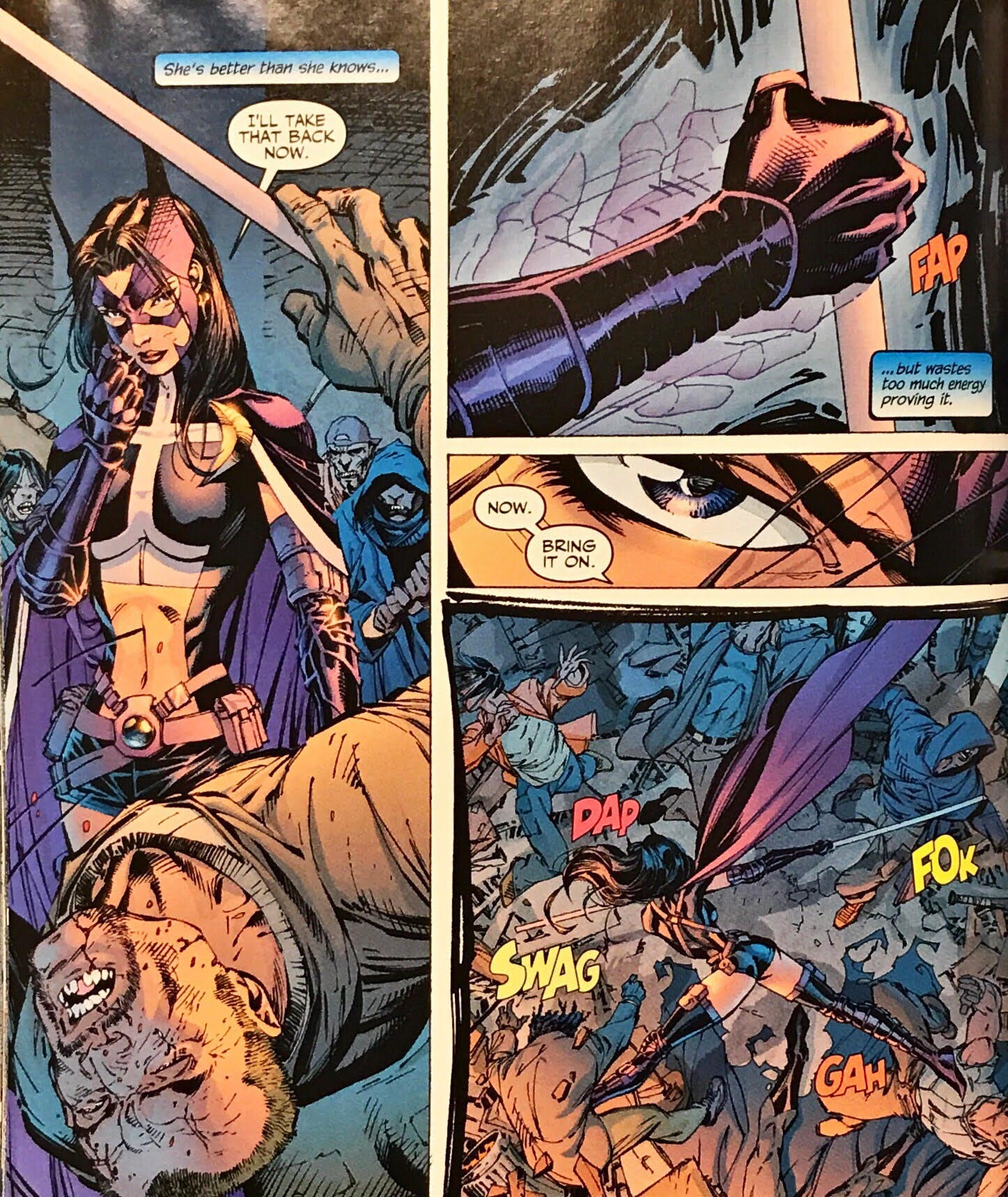

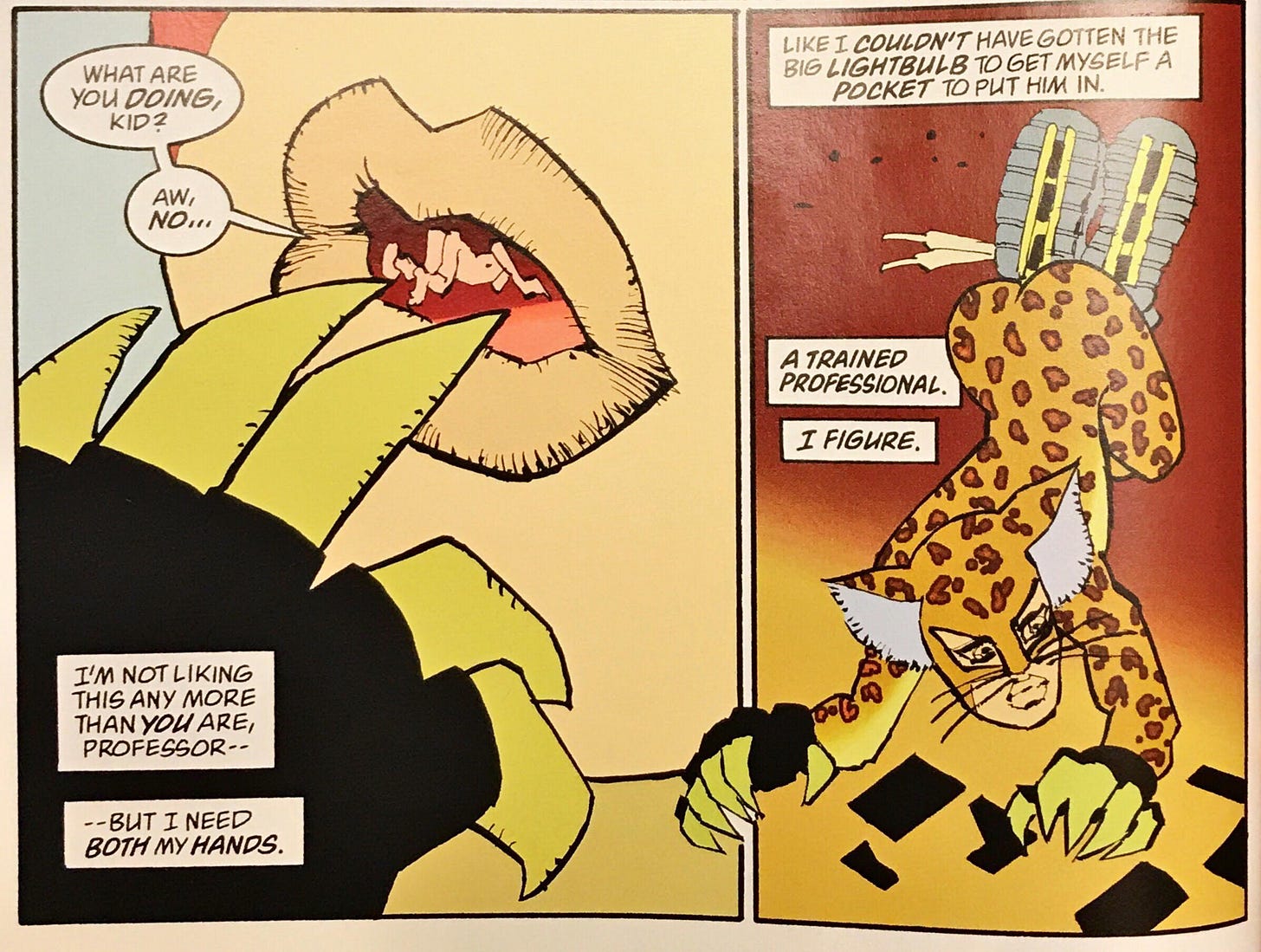

Taking the ever-present sidekick first, Loeb and Lee’s Hush explores the development of the Huntress, before her convoluted backstory problems post-New 52. Notice how Huntress is portrayed in a slightly more real than real manner. Her athleticism enhances the thoughts of Batman, currently lying on the concrete, and we see Batman’s sense of compassion and nurturing come through. Even in immense pain, his thoughts are on Huntress, on how he can encourage and direct her, even on how the two are similar. Miller also invokes the protégé motif, upgrading Carrie Kelly from the Robin character in The Dark Knight Returns to the new-ish Catgirl. Miller, known for his more shape-based artistic style, uses the art form to move away from the ideal, and even away from the real. The images are stark and meant to startle. This panel is all spectacle, from Kelly’s costume to the up close, awkwardly sensual act of the Atom hiding in her mouth. One of these is clearly an Aristotelian tragedy and the other a comedy.

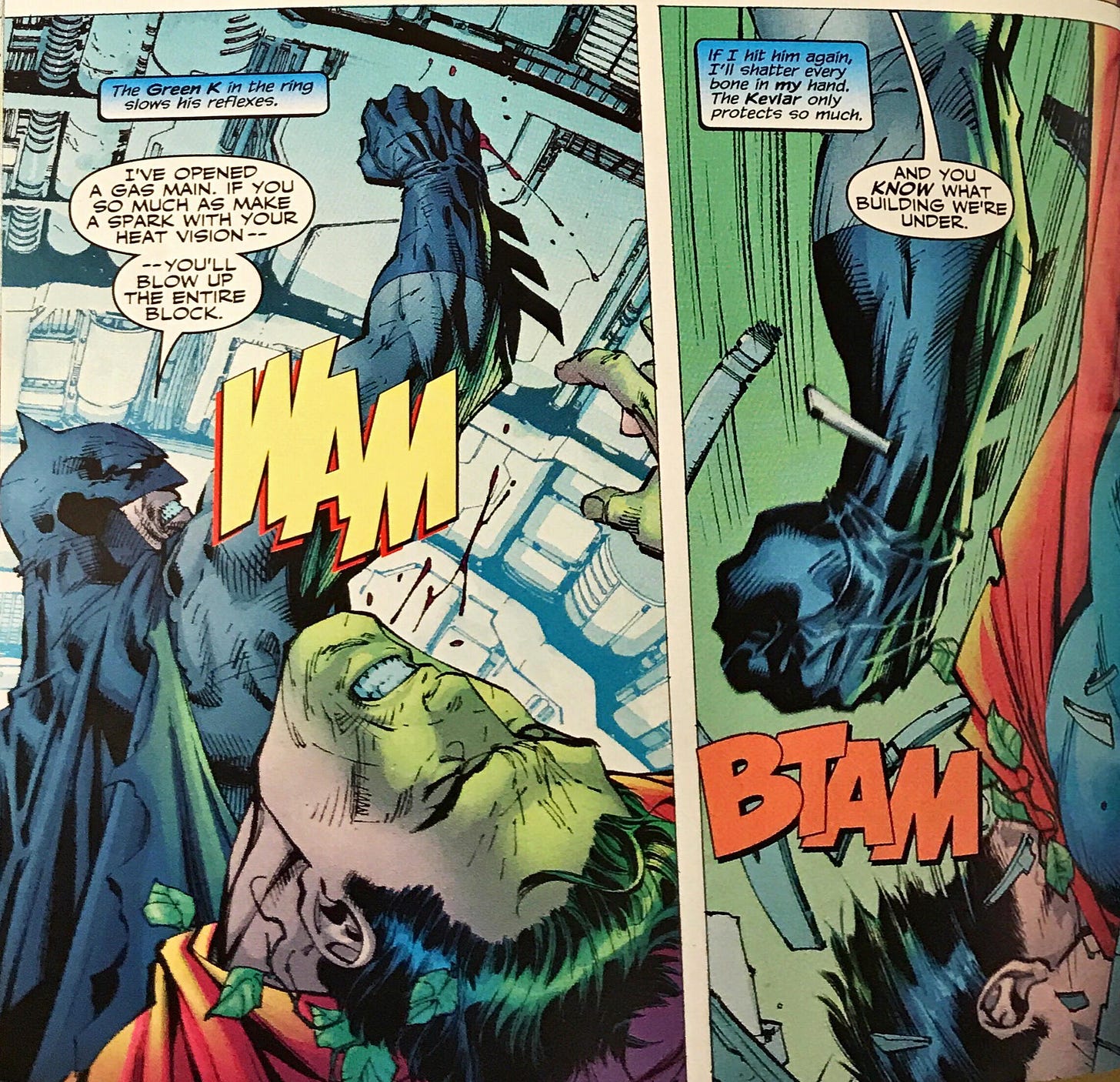

Next, we have the twin fights of Batman versus Superman. Again, Lee’s art invokes something higher than the real, even as Batman’s initial punch moves up rather than down. This is in contrast to Miller’s ever downwards panels, as Batman does not merely defeat Superman but punishes him, humiliates him. One of the most striking things is the silence of Miller’s images compared with the thought-heavy images of Loeb and Jim Lee. Batman is often defined by his intellect, his reliance upon his ability to think. But this is absent from Miller in many respects. For Lee, however, this is a defining characteristic which cannot be done away with, hearkening back to Aristotle’s hierarchy where thought indeed plays a vital role.

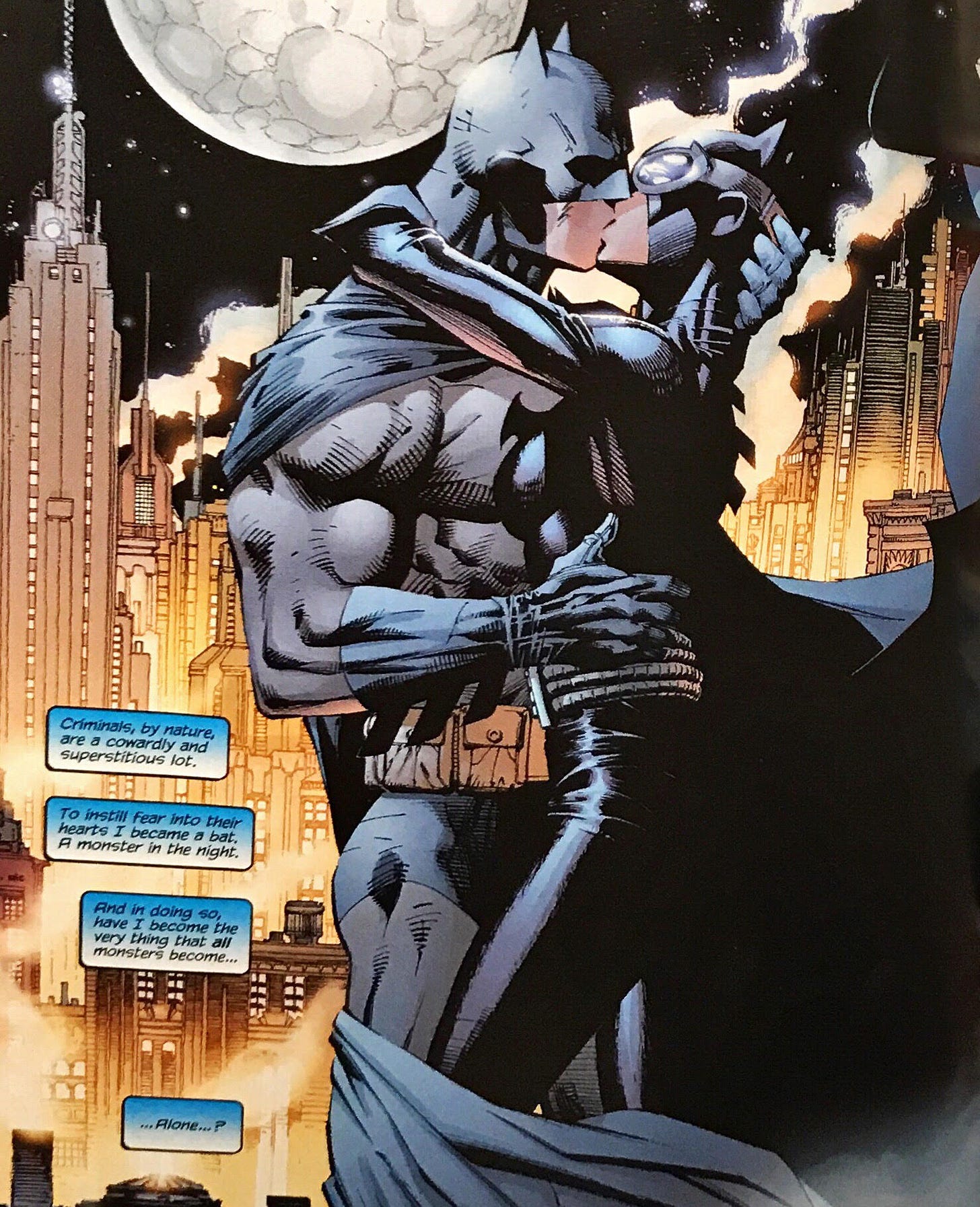

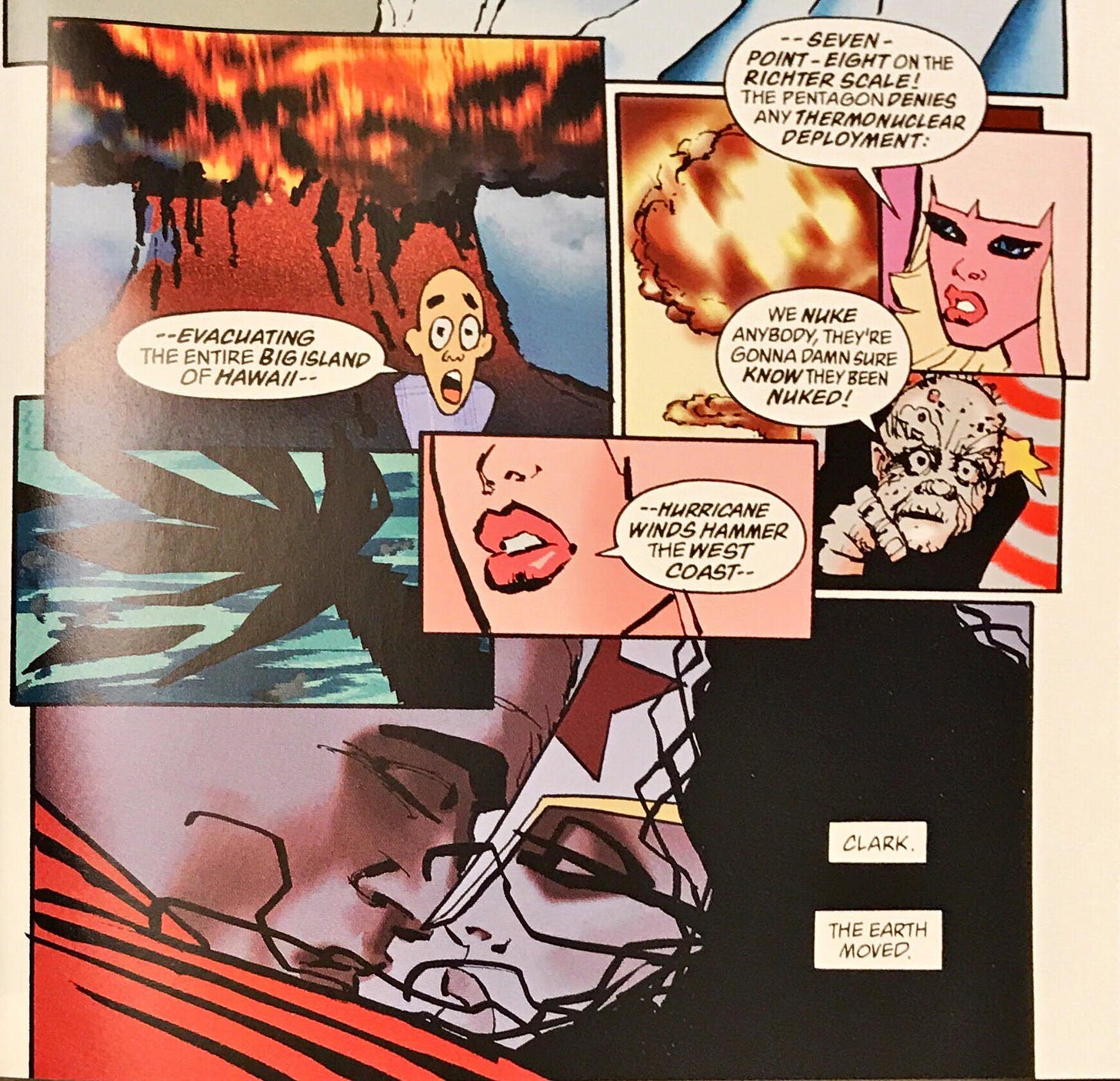

The final comparison draws upon the romantic entanglements in the comic world, but with different focal points. For Loeb and Lee, Batman’s relationship to Catwoman is essential to his character, but this scene again invokes the idea of Batman as a thinker rather than a man carried away with passions (note that this is the Golden Mean of Aristotle’s virtue theory). And what’s more, Lee’s emphasis moves the plot along in an important way, as the question of Catwoman’s reciprocation will have devastating consequences in the end of the story. For Miller, the spectacle wins the day as Superman and Wonder Women do something more than kiss, causing a minor earthquake in the process.1 All of Miller’s elements come together to create a comical scene out of something that, dare I say, ought not be so comical. Thus, in all these examples, Loeb and Lee’s tragic story encourages the reader to feel as Batman does and to imitate his principles, his virtues. Miller’s comedy, on the other hand, makes you wonder if even such a deranged Batman can deliver us from evil.

This exercise is not to permanently settle the categorization of Batman story arcs. Rather my goal has been to show that there is merit in retrieving old things for the understanding of new ones. As Umberto Eco once wrote of a similar endeavor, “Why should we not go and look for a modern theory of knowledge not (or at least not only) in Aristotle’s Analytics but also in the Poetics” (254)? The application may not have ever been predicated by Aristotle, but his theory holds remarkably true when analyzing the moral formation on display in the world of comics. And therefore, the pairing of Aristotle with Batman is fruitful for study, for it opens up a special lens towards understanding the permanent things which keep the Dark Knight relevant after 80 years and on into tomorrow.

References

Eco, Umberto. “The Poetics and Us.” In On Literature. Trans. Martin McLaughlin. New York: Harcourt, Inc., 2002. 236-254.

Loeb, Jeph, et al. Batman: Hush, Vol. I, New York: DC Comics, 2003.

———. Batman: Hush, Vol. II, New York: DC Comics, 2003.

Miller, Frank, and Lynn Varley. The Dark Knight Strikes Again. No. 1, New York: DC Comics, 2002.

———. The Dark Knight Strikes Again. No. 2, New York: DC Comics, 2003.

———. The Dark Knight Strikes Again. No. 3, New York: DC Comics, 2003.

Wainer, Alex M. Soul of the Dark Knight: Batman as Mythic Figure in Comics and Film. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2014.

This scene is particularly sad for me, since it also contains an overt reference to Ernest Hemingway’s For Whom the Bell Tolls. At least it would have made Papa laugh, I think.

If you found any of this interesting, you can read more along these lines in Hemingway and Comics and Batman’s Villains and Villainesses, where I contributed an essay to each.

(Ahem) Lee's art.