It is often more entertaining to argue about nonsense that has no basis, than it is to discuss things that can be examined with some degree of evidence from within. Beowulf is by no means exempt from this kind of debate; and much has been said about the poet, the style, the diction, as well as the religious ‘truth’ of the poem. The words of the Preacher ring true, that “there is nothing new under the sun.”1 The ways in which the academic readings of Beowulf have in some sense sucked the joy out of the beautiful poem was best described by J. R. R. Tolkien:

But his friends coming perceived at once (without troubling to climb the steps) that these stones had formerly belonged to a more ancient building. So they pushed the tower over, with no little labour, in order to look for hidden carvings and inscriptions, or to discover whence the man's distant forefathers had obtained their building material. Some suspecting a deposit of coal under the soil began to dig for it, and forgot even the stones . . . But from the top of that tower the man had been able to look out upon the sea.2

Tolkien’s point continues to ring true almost 100 years later, and his view shares much with the Preacher. But even with the Ecclesiastical viewpoint in mind, there remains much that can be learned and examined within the text of Beowulf. For instance, taking a brief look at the monsters within the text can yield a great deal about the poet’s Christian heirtage. Through such an examination, I believe that the reader will see a poem not steeped in a “strange combination of pagan myth and Christian belief,” but a text rich with understanding of Christian beliefs, in some manners an understanding that still eludes literary and biblical scholars today.3

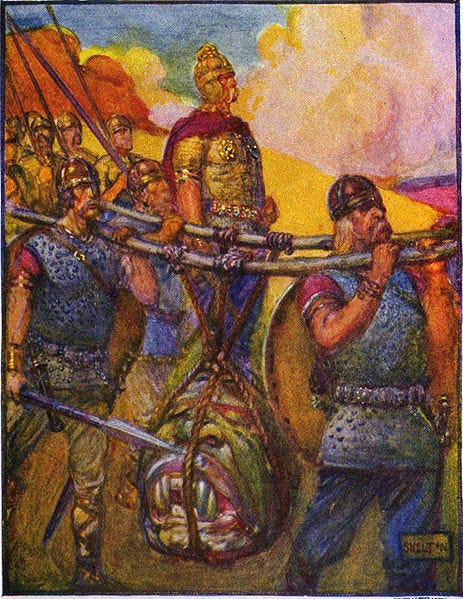

Easily one of the most gripping moments in the poem, Grendel’s first appearance provides the reader with lots of information to process: “Then the great monster in the outer darkness, / suffered fierce pain, for each new day / he heard happy laughter loud in the hall.”4

The immediate image of this creature is of one who does not abide by the joys of society. Only a few lines later the poet explains how Grendel is a “kinsman of Cain” who “knew not [God’s] love.”5 This genealogy presented by the author serves the same purpose similar genealogies provided in other Anglo-Saxon poems. The audience is being given the caliber of Grendel’s nature. But the implication that Grendel, the “huge moor-stalker,” is a direct descendant from the human offspring of Adam and Eve has in many ways served the argument that the Beowulf poet demonstrates how the “Christian and non-Christian belief dovetail in the minds of the Anglo-Saxons.”6

Although such a blending is a possible interpretation, another thought approaches Grendel under different circumstances. One of the issues plaguing the views on Beowulf’s monsters is the belief that such awful creatures should be beyond the Christian spiritual scope, particularly within the modern religious frame of mind. But the modern ‘realist’ approach to the breadth of Biblical scripture often falls short in interpretation. In a commentary on this very subject in his translation of Beowulf, Howell D. Chickering proposes the understanding that this ‘monster descendant’ theory stems from the passage in Genesis where, “the Nephilim were on the earth in those days, and also afterward, when the sons of God came in to the daughters of men, and they bore children to them. Those were the mighty men who were of old, men of renown.”7 Chickering connects the Book of Enoch to this concept and proposes that the “giants” of Genesis 6 were understood to be blood relatives of Cain.8 While an interesting theory, this does not answer the question of the poet’s Christian understanding sufficiently and needs further explication considering the Biblical Tradition.

There are other theories concerning the Nephilim, one in particular that deserves some examination when reading Beowulf. In his second epistle, Peter sheds some light on the subject:

For if God did not spare angels when they sinned, but cast them into hell and committed them to pits of darkness, reserved for judgment; and did not spare the ancient world, but preserved Noah, a preacher of righteousness, with seven others, when He brought a flood upon the world of the ungodly.9

The intriguing positioning of the condemned angels immediately before the comparison with Noah and the flood is not to be taken lightly. Within the scope of supernatural occurrences, it did not seem strange to many early Christians that the “mighty men” were spawned from an unholy union between fallen angels and mankind. While Biblical scholars continue to debate these passages, the idea that the “pits of darkness” or the “abyss” is often connected to demons.10 Luke’s Gospel claims that the demons “[implored Jesus] not to command them to go away into the abyss,” and John explains a vision of “the angel of the abyss; his name in Hebrew is Abaddon, and in the Greek he has the name Apollyon” (both words meaning “destruction,” something Grendel is quite proficient at).11 Such a creature sounds similar to a man-eating monster that would creep out of a swamp, “a murky swirl / of hot dark ooze . . . his dark stronghold.”12 Grendel’s connection to a fallen angel is strong within the text of Beowulf as he is called a “demon” by the author, and he is described as bearing “God’s wrath.”13 It would appear that Grendel has much in common with the demons of the Judeo-Christian world, and not so much in common with a singular ancient human.

However, that raises a question concerning the author’s use of Cain. Is the poet simply comparing the natures of Cain and Grendel, insinuating that the two are both murderous? While that is a possibility, another simple turn to the Bible will shed more light on this question. In the Apostle John’s first epistle, Cain is brought up and described in a very particular way, “that we should love one another; not as Cain, who was of the evil one and slew his brother And for what reason did he slay him? Because his deeds were evil, and his brother's were righteous.”14 John indicates that Cain had more in common with Satan than his did with his father Adam, while Adam was compared to Jesus in a number of passages. This similar nature shows up within the Beowulf text. Grendel is called the “shepherd of sins,” and is referred to as the “dark death shadow.”15 Chickering points out that these phrases mark references to the Devil in Anglo-Saxon poetry, and here they are used as descriptions for Grendel.16 This distancing is made even further by Grendel’s hatred for civilization, while Cain founded the first city.17 These things point to the author’s use of Cain as a deep understanding of Cain’s connection to Satan, a connection pointed out through Grendel.

By examining the possibility that the author connected Grendel to Satan through Cain, not because of the extra-Biblical Book of Enoch but rather because the author understood the connections within the Judeo-Christian Bible, readers find a demonstration of a superb Christian comprehensive knowledge. The blending of magical elements, of fantastic creatures, does not denote merely a blending of pagan and Christian cultures. Instead, this shows the extent to which modern critics, including those of a Christian background, have missed out on evidences within the Biblical texts that the medieval scholars were very attune to. And while many scholars today pick out the Old Testament sound of characters like Hrothgar, it is important to remember that Christianity was spread to the farthest reaches of the globe because of the words of Jesus, (and later on those of Paul, Peter, John, etc.). I believe that the poet displays an amazing grasp for New Testament concepts by his use of the ‘race of Cain,’ a grasp that many people today do not even come close to obtaining.

Ideas like this can be brought forward thanks in a large part to J.R.R. Tolkien’s extensive research on the topic of Beowulf. And as he once wrote, the tower is what matters, not merely the stones (my paraphrase). In the process of understanding the plausible connections that the author makes between the mythical in Beowulf and the supernatural in the Bible shows truly the amazing complexity that went into the telling and the writing of this treasure in English literature. In a certain sense, poems like Beowulf show how a pagan culture was ready and much more apt for a revolutionary idea like Christianity, not because it destroyed cultures and demanded the impossible, but because it appealed to “the old law” that Paul wrote about and understood so well.18 This new approach to Grendel’s connections to Cain and to Satan in no way proves the poem to be any more Christian than already believed to be. It does however shed light on the idea that the mythical and the supernatural were somehow appositional to Christianity. To the contrary, Beowulf remains a beautiful and moving tale because of its ability to bring Christian ideas into a realm ripe for hope in a dismal, often dark world.

Bibliography

Chickering, Jr., Howell D., ed. Beowulf: a Dual-Language Edition. New York: Anchor Books, 2006.

Heiser, Michael S. The Unseen Realm: Recovering the Supernatural Worldview of the Bible. Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2015.

Key Word Study Bible: New American Standard Translation. Red Letter edition. Chattanooga, Tennessee: AMG, 1995.

Major, C. Tidmarsh. "A Christian Wyrd: Syncretism in Beowulf." English Language Notes 32 (1995): 1-10.

Tolkien, J. R. R. “Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics.” In The Monsters and the Critics and Other Essays. Edited by Christopher Toilkien. London: HarperCollinsPublishers, 2006. 5-48.

NOTA BENE: This article is a revised version of “Beowulf's Monsters: Comparing the Mythology of Grendel, Cain, & Satan,” which was hosted at Academia.edu for many years (original URL: https://www.academia.edu/es/3727183/Beowulf_s_Monsters_Comparing_the_Mythology_of_Grendel_Cain_and_Satan)

Ecclesiastes 1:9 (NAS95).

Tolkien, p. 8.

Major, p. 1.

Beowulf, trans. Chickering, lns. 86-88.

Ibid., lns. 107, 169.

Ibid., ln. 103; Major, p. 9.

Genesis 6:4 (NAS95).

Chickering, “The Race of Cain”, in Beowulf, pp. 283-85

2 Peter 2:4-5 (NAS95).

Heiser, 97-100, 177.

Luke 8:31 (NAS95); Revelation 9:11 (NAS95).

Beowulf, lns. 849, 851.

Ibid., lns. 803, 712.

1 John 3:11-12 (NAS95), emphasis added.

Beowulf, lns. 750, 160.

Chickering, “The Initial Viewpoint on Grendel, in Beowulf, p. 285.

Genesis 4:17 (NAS95).

Beowulf, line 2330; Romans 2:14-15 (NAS95).