While much of this Substack is a kind of self-promotion, I rarely focus here on things that I publish elsewhere. I mention them, usually in my digest posts, but then I save the rest of my writing here for other things (i.e. book reviews I’ve been sitting on, movie and music writings, shorter intellectual pieces). Most of it is stuff I think my readers will find interesting though, and to that end, I want to offer some thoughts on a forthcoming publication.

I’m quite proud to say that I have new essay coming out in The Consortium Journal: A Journal of Classical Christian Education. The essay was born from necessity and love: a friend asked if I would give a talk on Williams because he needed another panelist, and I love Williams’s fiction (particularly what it can bring to the classroom). The panel was organized for the 2024 Ciceronian Society meeting, and it was a fun time with perhaps the liveliest Q&A session I’ve enjoyed at an academic conference thus far in my career.

The whole issue is dedicated to the Inklings and specific thoughts about their importance to the Classical Christian classroom. I have no doubt I could have submitted my essay to other journals, but I genuinely thought the best place for this piece was somewhere that actual teachers might read it and make use of my thoughts in their own classes. And the Table of Contents demonstrates just why this volume will be helpful to classical educators, and why I like publishing in The Consortium.

- , “The Inklings and Classical Christian Education: An Example of Christian Humanism”

Annie Crawford, “The Mind of a Reader: A Trinitarian Framework for Reading and Teaching Literature”

- , “The Ascent of the Imagination: Charles Williams in the Classical Christian Classroom”

- , “C. S. Lewis in the Classical Classroom: Deepening Appreciation for Reality”

- , “Reading Tolkien in the Classical School Classroom”

- , “Owen Barfield, Poetic Language, and Classical Education

- , Book Review: Alistair E. McGrath’s Deep Magic, Dragons and Talking Mice: How Reading C.S. Lewis Can Change Your Life

Joe Carlson, “Loving What Lewis Loved: How Lewis Led Me to Translate the Divine Comedy”

Christiana Hale, Excerpt from Deeper Heaven: “Mapping the Universe—The Medieval Cosmos”

The rest of the Ciceronian Society panel is here as well, which is a nice way to continue our collaboration. But I am confident in the additional entries and their contributions to the classroom. Scott Postma’s writings are always a nice combination of insight and practicality. Annie Crawford’s essay on Sayers is very much worth your time (and was presented at the 2023 Ciceronian Society conference). Joe Carlson’s essay should prompt you to dig into his new translation of Dante’s Divine Comedy (of which I have read The Inferno and can vouch it is a worthwhile rendering). Christiana Hale’s excerpt is one of the best sections of Deeper Heaven (a book of immense value for teachers). And I’m looking forward to Karla Memmott’s review, particularly since I know she brings practical experience to bear on her academic writings.

In fact, looking it over, I think my contribution might be the bottom in terms of importance. But I still think you should give it a read! Without giving too much away, this short excerpt is a nice summary of why I defend Williams and his fiction in the classroom:

Putting biographical studies aside, the far more interesting set of questions begin with a practical one: “what kind of fiction does the Classical Christian student need?” Recognizing that the world outside the classroom is not creating a forest of transcendence that needs to be trimmed back but instead bombarding Classical Christian students with sustenance, this present age needs stories where “there is no frontier between the material and spiritual world.”1 In this way, Williams’s novels accomplish what Lewis describes as “irrigating deserts.”2 Students at Classical Christian schools read Plato, Aristotle, Solomon, and other sages from the Ancient world. They study Boethius, Pascal, Alexis de Tocqueville, all of which is right and good. Having taught these very books for many years, one of the richest experiences is when a student discovers a philosophical and intellectual concept embedded in some work of the imagination. Students discuss love in Platonic terms and then read Till We Have Faces only to understand it wholly anew. They read Plutarch’s Lives and then come face-to-face with Caesar in Shakespeare. Such moments are necessary and even baked into the formula that governs most Classical Christian schools. As Chris Butynskyi writes in his book on the Inklings: “Imaginative literature allowed . . . the potential for insight into the apparently incomprehensible.”3 This is one of the strengths of the Inklings as a group, and of Williams’s fiction specifically.

Even now I can recall just how much fun this project was. It was fun to research, to write, and to deliver it to our audience in Plano. I imagine it was the same for most of the pieces in this journal, and I encourage anyone interested in teaching the Inklings in the Classical Classroom to give this whole volume a read. I firmly believe that every entry will have something that a teacher can make much use of in their pedagogy, in their reading, and in how they introduce students to the Inklings. And you might have a little bit of fun along the way.

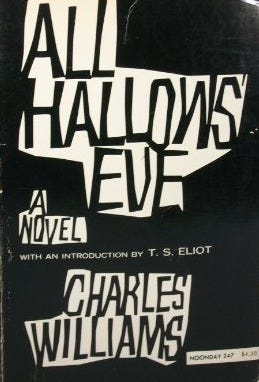

T. S. Eliot, “Introduction,” in Charles Williams, All Hallows’ Eve (Grand Rapids, MI: Williams B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1989), xiii.

C. S. Lewis, The Abolition of Man (New York: HarperCollins, 2009), 38.

Christopher Butynskyi, The Inklings, the Victorians, and the Moderns: Reconciling Tradition in the Modern Age (Lanham, MD: Farleigh Dickinson University Press, 2020), 69.