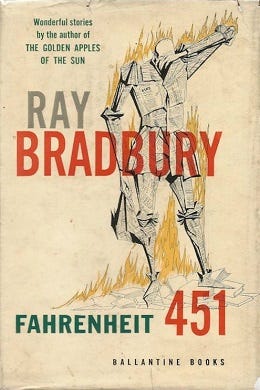

One of the writers who came into his own during the era that speculative fiction was making its mark was Ray Bradbury.1 Bradbury explored numerous worlds in his writing, but the world of Fahrenheit 451 stands out. It is worth noting that the moral action of Guy Montag does not begin in his own story, but rather starts in a short story written previously. “The Pedestrian” briefly charts the rebellious walking of Leonard Mead, and his subsequent arrest.2 The world in which Mead finds himself is one where the cultural norm is to stay at home, watch the viewing screens, and keep to oneself. But Mead pushes against this by “just walking.”3 This small act is indicative of a life which has cut Mead off from his neighbors, even leading him to declare that “nobody wanted me” when he is questioned about his marital status.4 Here the conflict of rival traditions is made manifest. As a writer, who lives in a world where “magazines and books didn’t sell anymore,” the tradition that had defined Mead’s life is in full blown conflict with that of the culture around him.5 Unfortunately for Mead, his own community does not embody the “Neo-Aristotelian” belief that “deliberation” and “practical reasoning” is only made feasible when “the use of force or the threat of force against innocent individuals” is forbidden.6 Mead’s community is not open to dialogue about rival traditions, and his story ends with a sense of despair.

We can see here a connection between speculative fiction and virtue theory as explored by Alasdair MacIntyre: a love of the written word. Writing is the way in which experiences are passed down, “for experience itself seeks and finds words that express it.”7 The intricate connection here is so thoroughly impossible to disentangle that Hans-Georg Gadamer declared, “Verbal form and traditionary content cannot be separated in the hermeneutic process.”8 Even though the world around Mead has given up on the written word, it is the same thing which gives Mead a separated perspective; and this singular fact makes him dangerous to the culture. His arrest stems not only from the fact that he likes to walk instead of sitting in his home watching, but because his profession has widened his horizon to the point that he can see what the prevailing tradition is not the only one to consider.

Bradbury would not leave the story there, however. Building out of a world where it is illegal to walk, Bradbury next envisioned how this same world might also make it illegal to read. In the character of Guy Montag, the focus would shift from walking to, in fact, reading. If Mead is dangerous because he once wrote, Montag even more so because he has a desire to understand books long before he has even opened one.9 For a year he had been collecting books, not reading them, and he was unable to give his wife Millie a reason until he watches a woman burn alongside her books.10 He realizes that there is something inside the books that might at least get them “half out of the cave,” but as Granger, the living embodiment of Plato’s Republic, tells him later, “you can’t make people listen.”11 Montag’s awakened passion initially believes that books will save the world, but that idea will never do. It must begin with the people who have bought into the vision of life represented by Millie, the television addled, the drugged-unto-death, for until they “come round in their own time, wondering what happened and why the world blew up under them,” not much of anything is going to change.

It is worth noting that the tradition of the written word overrides, and undermines, those rival traditions that go without such trappings. Bradbury’s antagonist, Beatty, stands in for the wrong ways in which those who have encountered the past might twist a rival tradition to their own ends. When Montag’s wife reports him to the firemen, Beatty attempts to turn the words of the past back on him.12 Beatty is the kind of bureaucrat that must be considered stupid, not because he lacks the capacity to reason or debate, but because he cannot make application of the past traditions in a way that produces a good result.13 His smile in the face of certain death shows just how little he truly understands the inner workings of the individual. Montag overcomes his wiles by exerting the authority of words over top Beatty’s recriminations, telling him, “We never burned right,” a term that means quite a lot for Montag.14 For if Montag had been cut off from the past, what could he possibly mean by using the word “right”?

Although it has roots that stretch back to Sophocles and Aeschylus, speculative fiction is understood to have come of age in America during the middle decades of the 20th century. For further information, see Robert Heinlein, “On the Writing of Speculative Fiction,” in Writing Science Fiction & Fantasy: 20 Dynamic Essays by the Field's Top Professionals, (New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 1993), 5-11.

Ray Bradbury, “The Pedestrian” in A Pleasure to Burn: Fahrenheit 451 Stories (New York: William Morrow Paperbacks, 2011), 156-161.

Bradbury, “The Pedestrian,” 159.

Bradbury, “The Pedestrian,” 160.

Bradbury, “The Pedestrian,” 159.

Alasdair MacIntyre, Ethics in the Conflicts of Modernity: An Essay on Desire, Practical Reasoning, and Narrative (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2016), 56.

Hans-Georg Gadamer, Truth and Method, eds. Joel Weinsheimer and Donald G. Marshall. Rev. 2nd (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2013), 435.

Gadamer, Truth and Method, 457 (emphasis in original).

Ray Bradbury, Fahrenheit 451, 60th Anniversary (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2013), 61-63.

Bradbury, Fahrenheit 451, 36-37.

Bradbury, Fahrenheit 451, 70; 146.

Bradbury, Fahrenheit 451, 102-113. These final moments between Montag and Beatty are some of the most well-crafted, as Beatty constantly misquotes or misuses the literature that he abhors to confuse the newly converted Montag. Beatty’s early remark, “The Devil can cite Scripture for his purpose,” says more about Beatty than it does the books he rails against (103).

Alasdair MacIntyre, After Virtue, 3rd edition (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 2007), 155. As MacIntyre points out, such a person might do well in a Kantian system, but not in an Aristotelian one.

Bradbury, Fahrenheit 451, 113.

I just rereading F451 right now! Such an amazing work. Thanks for this, Sean.