Making It New in the Shadow of Giants

How The Odd Friendship of George Santayana & Ezra Pound Still Shapes American Writing

I’ve done quite a bit of work over the last couple of years connecting the New Humanist movement of the early 20th century to a rival-though-related movement in Literary Modernism. While I don’t know if I’ll ever find the time to fully return to this study in the future, I found the way individuals connected across these theories of literature fascinating to the point that it seems worth sharing. In particular, the example I want to explore a bit below shines light on some of the more interesting peculiarities common in modern American writing.

Just prior to World War I, it was a reasonable question to ask if American’s had found their literary voice. Though today many will point to Mark Twain or Walt Whitman as a definitive answer to this question, others were quick to say, “not so fast.” Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, who was sometimes mentioned in this debate, tried to explore the question in his “The Literary Spirit of Our Country.” But even he concluded it was still too early to tell. I’ve explored the way much of this early debate kicked off in an essay that the good folks at Pietas were kind enough to print, so I won’t rehash the details here. In that article, I argued that George Santayana, in a philosophical argument with thinkers like Irving Babbitt and Stuart P. Sherman, had divided American writing into the “Strong” and the “Weak,” and that this was largely based on how they engaged the Great Tradition. Santayana dubbed his Traditional opponents as “The Genteel Tradition.”

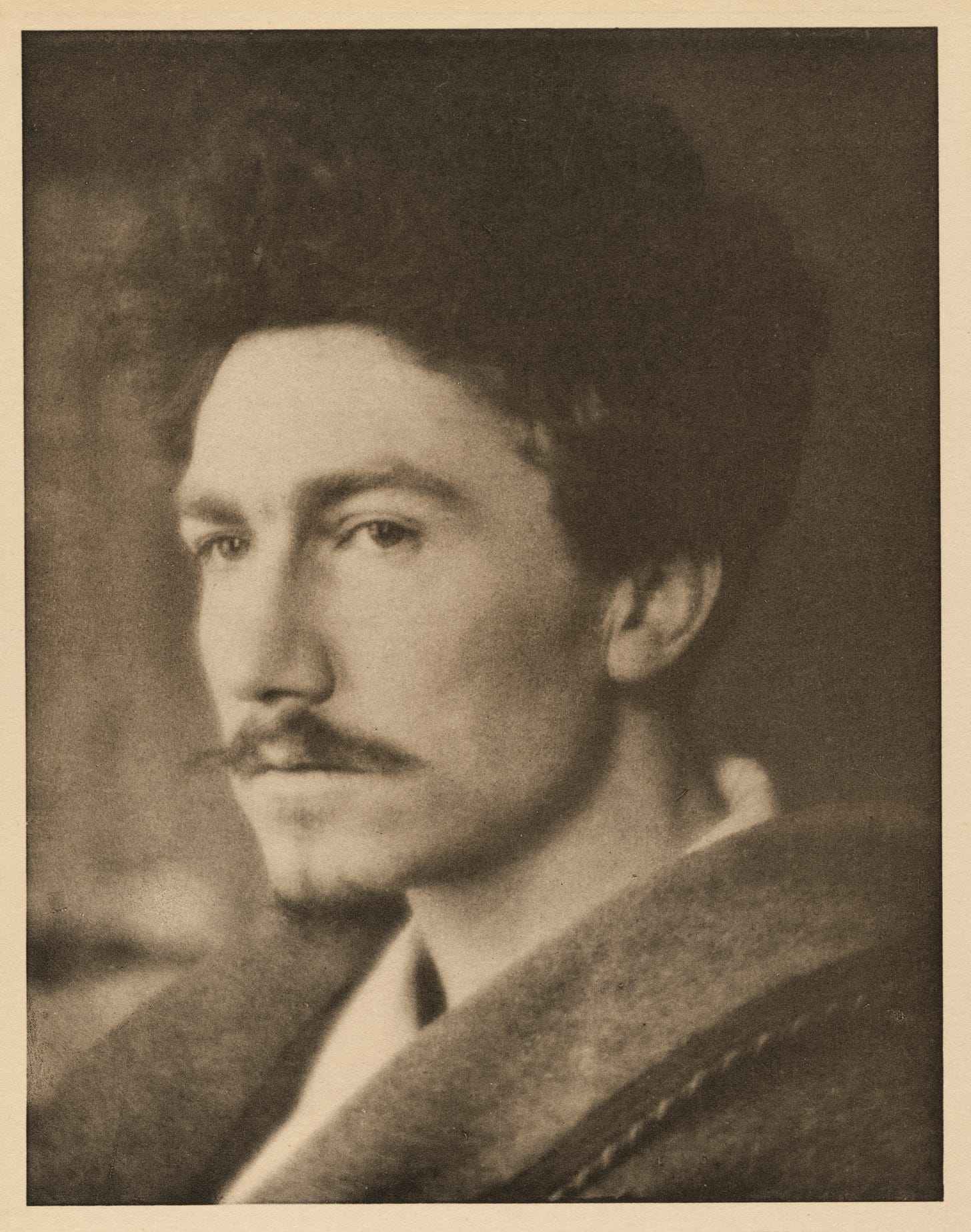

Whatever literary critics and publishers might say, American writing continues to live in the shadow of the Modernist movement that came to prominence in the 1920s. One of the reasons this grouping of authors continues to set the mood for so many stems from the wide array of authors who were connected to it, even if said authors were completely at odds with one another. Differences in style, like that which exists between William Faulkner and Ernest Hemingway, make it difficult to say that Modernism is clearly identifiable as one thing, though Ezra Pound’s famous (infamous?) phrase “Make It New” remains one of the key components of understanding any branch of Modernism.1

In fact, Pound serves as the best, and most unexpected, transition from the arguments over the Genteel Tradition to the birth of Literary Modernism. The strangeness of Santayana and Pound’s friendship has been documented thoroughly by John McCormick and Martin Coleman, but there is something beyond the epistolary evidence to bring these two thinkers to bear on American Literature’s trajectory.2 Pound may have viewed Santayana as more sympathetic to the Modernist cause than the aging philosopher was, but Pound was right to see in Santayana’s critique of literature and culture someone who was also interested in “making things new.”3 Pound’s vision of Modernism attempted to redeem the Tradition that Santayana treated skeptically and the New Humanists sought to revive. Pound, in this way, acted as the kind of poet that Russell Kirk described as one who, “lives in a tradition,” making it possible for him to “become a prophet; the great mysterious incorporation of the human race speaks through him, so that he says more than he comprehends.”4 Santayana’s wonderings in his letters, if anyone understood Pound when he spoke, are not intended as an affirmation, but such comments coupled with his concern for an incarcerated Pound suggest that Santayana had a deeper affection for Pound than he often showed.5

Pound’s central relationship to the Modernist movement helped define it. His connection to T. S. Eliot, who also affiliated with the New Humanists, ensured that the burgeoning literary development would draw from the Western Tradition broadly conceived. Thus, Pound did not draw directly from the Moral Tradition and the Church, but he did draw from the same wells in the hopes of inspiring something new. This is most clear in Pound’s Cantos, which correspond to Dante’s Divine Comedy. Santayana, in an uncharacteristically gentle letter, offered to send Pound a copy of his Realms of Spirit to help Pound as he wrote his Dante–inspired poems.6 Santayana says he was flattered by his most recent visit from Pound in that same letter, though he confesses he doesn’t understand what Pound means when he talks. His offer to send Realm of the Spirit after Pound requested guidance seems genuine rather than cynical, as his earlier mentions of Pound had been in his letters.7

Though irreverence for the past is sometimes used to exclude authors from the group, Pound and T. S. Eliot both “knew much of the history of Western poetry” and “incorporated much of that history into their own verses,” but their place amongst the Modernists remains steadfast.8 Pound, and Eliot and Hemingway alongside him, saw “the goal of the modern artist not as a break with tradition, but as a recapturing of tradition, in circumstances for which the artistic legacy has made little or no provision . . . If, in modern circumstances, the forms and styles of art must be remade, this is not to repudiate the old tradition, but in order to restore it.”9 Whatever else they must be, Modernists begin with a deep appreciation of the ancients and medievals. They are not authors cut off from the past, but rather artists who seek to rekindle the fires of old, to ignite new stories and forms drawn from the old, so that those living in the present may understand their own moment better. While “books often reflect the spirit of the age” simply due to the facts of context, Santayana and Pound’s friendship shows that there’s more than one way to understand the effects of Modernism.10 And every American author today, even when attempting to write something “genre-defying,” still finds themselves taking part in the same conversation.

Michael Levenson, “The Shock of the New: Why we’re still struggling to make sense of the modernists,” The Atlantic (October 2013): 39.

John McCormick, “George Santayana and Ezra Pound,” American Literature 54, no. 3 (October 1982): 413–433; Martin Coleman, “‘It doesn’t . . . matter where you begin’: Pound and Santayana on Education,” Journal of Aesthetic Education 44, no. 4 (Winter 2010): 1–17.

McCormick, 419–420.

Russell Kirk, Enemies of the Permanent Things: Observations of Abnormity in Literature and Politics (Providence, RI: Cluny Media, 2016), 55.

McCormick, 422, 426.

George Santayana, The Letters of George Santayana: Book Six, 1937–1940, ed. William G. Holzberger, vol. 5 (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2004), 344.

McCormick, 414–415.

Peter Hays, “Hemingway and Wharton: Both Modernists,” in Wharton, Hemingway and the Advent of Modernism, ed. Lisa Tyler (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2019), 25–26.

Roger Scruton, Beauty: A Very Short Introduction (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), 170.

Kirk, Enemies of the Permanent Things, 64.