My mind often wanders, and a topic that frequently recurs to me is that of literacy. I don’t mean this in the narrowly defined meaning that it’s used today, denoting the basic ability to read and write (a usage which became common in the 1880s, trending in line with the chart below). Rather, I mean the older usage which more properly derived from “literate,” meaning an educated person. To measure someone’s literacy was to measure their level of education.1 To possess literacy was to possess an education, not the bare essentials of communication for life.

The reduction of this term to such a low baseline is part of a broader trend to equate education to a bare-bones aspect of life. Classical Education, in which I have a vested interest, is trying to redirect this trajectory. I’ve begun working on a project related to what students know about the virtues, a field which retains that older use of the word by referring to this subject as “virtue literacy.” While I anticipate having some things to say about that in the future, I’ve recently begun to think that Sir Philip Sidney’s excellent defense of the reading life serves as a starting point for this conversation.

Sydney is arguably the first modern exponent of what we would today consider proper literary theory. In his Defense of Poesy, he states that among the Romans a poet was called vates, which is as much as a diviner, a foreseer, or a prophet.2 But in the 21st century, poetry does not have the same value. Consider the normal order of publication even up into the mid-20th century: authors would publish a collection of poetry before moving onto prose. This is true even of authors like Ernest Hemingway, who was never known as a poet despite the 1923 publication of Three Stories and Ten Poems for his debut work. For most of recorded history, to be a writer of note meant first finding success as a poet.

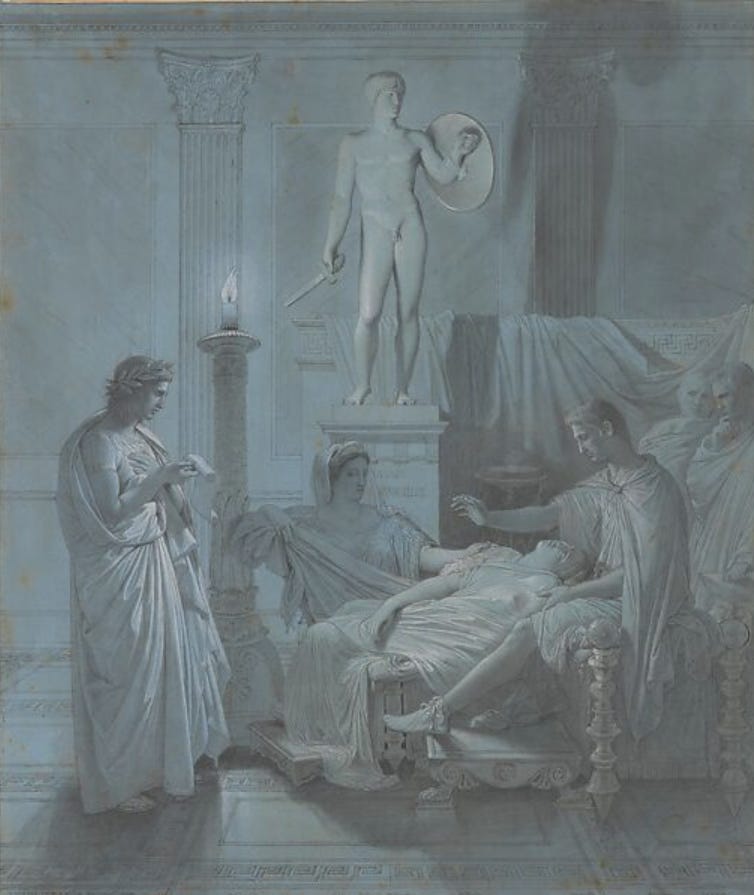

I want to be clear. This doesn’t mean that only poets have been successful, or that great prose writers of the past were also great poets. This is more to explain that the expectation for anyone serious about writing and reading would begin with poetry. This is part of why, for the Ancients and the Medievals, the poet was something akin to a prophet. Sidney wasn’t the first to make that connection, with Horace’s “sacer interpresque deorum” Orpheus playing a role both poetic and civic.3 It’s worth wondering about how this has changed in our hypermodern age. I think you could muster an argument that it hasn't changed completely, but that it has shifted in a way that’s significant.

What Horace hints at here, and what Sidney seems to have in mind as well, is that the poet is keyed into the culture and surrounding community because they are connected to the Divine. Attempts at poetic communication are attempts to describe or relate or draw others into the Transcendent. By contrast, in our own day, the “poet” who most holds a public office is the popular musician, and these “poets” are more tapped into the imminent rather than the transcendent, describing what is present with us already rather than what’s outside of us.

This helps to explain why the author of today no longer begins with poetry. Western culture seems to view poets, not as prophets, but rather as intellectuals. Consider how often you’ve heard someone say, “poetry is too hard to understand.” Such would have been a rare, possibly unheard of, statement in the days of Homer or Virgil, because the poetic was also the popular.

I’ve heard it posited that this shift is the result of secularization. Perhaps. But is today’s hypermodern culture really more secular (and by corollary, less sacred) in the public square? I’m not convinced it is. One need only look at the near cultic following that someone like Taylor Swift has to think that maybe the public square is still rife with the sense of the sacred (even if not with the sacred proper).4 This isn’t just a new thing, either, though the following of Swift may be unique in some ways. Screaming fans of the Beatles, the Beach Boys, and Johnny Cash also suggest that this tethered relationship with musicians as the 20th century conduit for the sacred goes back quite a way.

Tying this idea back into the notion of literacy helps us to see the need for a return to the poetic in the sense that Sidney described it. Consider first the literacy rates in America. The most common number bandied about today is that 80% of adults in the U. S. are literate (again, going back to that basic ability to read and write).5 It’s possible that the number is closer to the 2014 estimate of 92%.6 It also seems that most adults read at what would be considered a 6th grade reading level (though this standard is debatable). That means that the average American, even in a very accessible translation, will struggle to understand Virgil. Whereas the average Roman citizen of any rank could have read Virgil and understood him.

We live in a world where words inundate us, yet we seem to lack the ability to comprehend them. And as a result, we shun the form of writing which once provided the shared culture of humanity across social classes and age. We see words on billboards, on phones, even on clothes. There are words everywhere. Yet despite this superabundance, comprehension is lower than it has been since we started measuring these things.

Poetry’s function, according to Sidney, goes beyond mere entertainment (which seems to be what music is reduced to) and it is more than mere reading enrichment (like the educationalists think). The poetic is that connection point for all aspects of life and community, bring the sacred and secular into harmony, stimulating the imagination and our capacity for invention. And it’s something that we seem to be losing more and more each day.

I think it’s best to let Sidney himself summarize what the recovery of a proper poetic is necessary for us to truly become a literate people once again. Only by such a return can we,

believe, with Aristotle, that [the poets] were the ancient treasurers of the Grecians’ divinity; to believe, with Bembus, that they were first bringers—in of all civility; to believe, with Scaliger, that no philosopher’s precepts can sooner make you an honest man than the reading of Virgil; to believe, with Clauserus, the translator of Cornutus, that it pleased the Heavenly Deity by Hesiod and Homer, under the veil of fables, to give us all knowledge, logic, rhetoric, philosophy natural and moral.

It’s worrisome that we may have reached a point where we have no concept of what he’s talking about here. But the fact that we can pick up Sidney’s writing today, understand it, and engage its ideas in conversation, provides a spark of hope.

This usage seems to date to at least the 15th century AD (probably the first half of the 1400s). https://www.etymonline.com/word/literate

Philip Sidney, A Defense of Poesy. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/1962/1962-h/1962-h.htm

Horace, Ars Poetica, in Satires, Epistles, and Ars Poetica, The Loeb Classical Library (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1926), ln. 391, “the holy prophet of the gods” (trans. Fairclough).

This article is a good example of what I mean: https://news.northeastern.edu/2025/01/03/taylor-swift-eras-tour-religious-pilgrimage/.

This number is from The National Literacy Institute, though I could not find where they go their data: https://www.thenationalliteracyinstitute.com/post/literacy-statistics-2024-2025-where-we-are-now.

The NCES data for 2014 is available, and when their analysis is reduced to its most basic level, the 92% number describes that bare-bones definition I mentioned earlier: https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2019/2019179/index.asp.