Political Conversions, Religious Conversions

A Brief Look at Hasmonean Reform and Forced Circumcisions

I originally published this article on my Academia.edu profile some years ago. The article consistently ranked as one of my most read pieces on Academia.edu, but that version lacked in a couple of ways, primarily in the ways my own views changed as I moved away from my shallow view of faith and politics. And it contained grammatical errors that bothered me. When I made the decision to start a Substack, I pulled all my “non-published” work from Academia’s website so that I could go back through them and give them a more polished life here. I wrote this for a graduate class before I started teaching the Apocrypha to 10th grade students. But once I started teaching these books, I became even more convinced of the need for Protestants to better understand the period leading up to Christ’s Incarnation.

Introduction

As with all eras, during the time that Jesus Christ ministered in Israel, political and religious ambitions were often at odds, at once challenging and preserving the status quo. Preserving the order of things was a primary goal for much of Jesus’ opposition, as evidenced by Herod’s attempt to kill Him and the frequent traps set for Him the Jewish leaders of the day (cf. Matt. 2:18-18, Luke 9:18-27). Reading the Gospels paints a picture of religious and political leaders who feared the very people they ruled, as leaders who were constantly oscillating back and forth between personal ambitions and the demands of the multitude. The tensions that plagued the people in Jesus’ time had roots that stretched back to the Intertestamental period that began after the Jewish exile ended. The events that unfolded around Palestine had a profound effect of te hierarchical relationships that existed between the Jewish people and the elite among them, Jewish and Gentile in nature, which also affected the ministry of Jesus. The spiritual reform that Jesus taught struck fear in those who had worked hard to maintain their positions of power. A brief look at the historical context around the Maccabean Revolt offers interesting insights into the world that Jesus ministered.

Breaking a Nation: Religious Persecution Takes Hold

Needing to unite his empire, Alexander the Great went to great lengths to create a sense of brotherhood among his subjects. Relocating people groups so that would intermarry, introducing conquered Persians into his army, founding cities in his own honor, and promoting Greek customs and language were all methods used by Alexander to harmonize his people. While this worked as a whole, the Jews proved to be strongly resistant to such attempts at integration. Alexander’s son, Antiochus IV, had to put an end to rebellions in Palestine and as a result he forced sacrifices to the Greek gods upon the Jewish people and he desecrated the temple. I Maccabees opens with the demands of Antiochus on the Jewish people:

Then the king wrote to his whole kingdom that all should be one people, and that all should give up their particular customs. All the Gentiles accepted the command of the king. Many even from Israel gladly adopted his religion; they sacrificed to idols and profaned the sabbath. And the king sent letters by messengers to Jerusalem and the towns of Judah; he directed them to follow customs strange to the land, to forbid burnt offerings and sacrifices and drink offerings in the sanctuary, to profane sabbaths and festivals, to defile the sanctuary and the priests, to build altars and sacred precincts and shrines for idols, to sacrifice swine and other unclean animals, and to leave their sons uncircumcised. They were to make themselves abominable by everything unclean and profane, so that they would forget the law and change all the ordinances. He added, “And whoever does not obey the command of the king shall die.”

In such words he wrote to his whole kingdom. He appointed inspectors over all the people and commanded the towns of Judah to offer sacrifice, town by town. Many of the people, everyone who forsook the law, joined them, and they did evil in the land; they drove Israel into hiding in every place of refuge they had. (1 Macc. 1:41-53, NRSV)

The Jewish people faced a persecution that threatened to wipe out their culture and their heritage as the chosen people of God under Greek rule. However, just as the Lord preserved a remnant of “7,000 in Israel, all the knees that have not bowed to Baal,” a small group of rebels would rebel against the Greek Empire and change the course of religious and political life for Israel thereafter (1 Kings 19:18, NAS95).

Taking It Back: Fighting for Religious Freedom

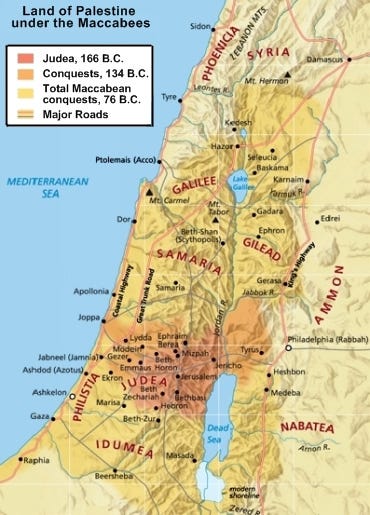

Of the most momentous events during this time, the Maccabean revolt had the greatest hand in establishing a solid political and religious structure for the small nation of Jews.1 Following the death of Alexander the Great, civil war erupted within the Greek Empire, resulting in a kingdom to the North governed by the Seleucid rulers and a kingdom to the South governed by the Ptolemaic rulers. With Judah located between the two warring States, turmoil engulfed the little nation as it was conquered and reconquered by the various kings seeking to build their empire. After the Seleucids conquered Egypt, war raised its head again with the death of Antiochus IV. Two successors, Lysias and Phillip, divided the kingdom for a time. After two previously failed rebellions, the Jews saw their opportunity to retake their land. Under the guidance of Judas Maccabee, the son of a priest who had begun a small rebellion in the north of the country, the Jews launched several successful campaigns against the Seleucids and eventually took Jerusalem. Lysias sought to quell the Jewish rebellion and he led his army into Jerusalem without much resistance, killing Judas’ brother Eleazar at Beth Zechariah.

At the same time, Phillip was marching towards Egypt to settle the issue of Antiochus’ successor. This caused Lysias to make a hasty withdrawal from Jerusalem. Lysias agreed to give the Jews religious freedom in exchange for a peace accord. However, to retain some semblance of control, Lysias appointed the new High Priest. His choice was Alcimus, a Hellenistic Jew, who was accepted at first because he belonged to the family of Aaron. Alcimus did not remain in favor long, as he sought to Hellenize the Jewish people and Judas Maccabee expelled him from the land after only two years. While the politically chosen High Priest did not hold office for long, the effects of Lysias’ actions would ripple throughout the rest of Israel’s history continuing to be a factor eventually under Roman rule.

Religious Politics and an Independent Israel

As the Maccabean revolt took its toll on the nation of Israel, and on the various empires vying for control of the region, an end to the rebellion was seen in the rise to power of the only remaining sibling of Judas Maccabee, Simon. It was Simon who was finally able to achieve what his brothers had so fervently fought for: independence. In a political alliance with Syria, Simon began the dynastic rule of the Hasmonean kings recognized first by Syria’s king Demetrius II. The significance of the Hasmonean line cannot be overstated:

The time of the Maccabean Revolt was one of constant turmoil and upheaval. Instability and uncertainty were the order of the day. However, with Simon and his ancestors, an hereditary line was set up which at least gave an appearance of stability to the nation of Judea. This was the Hebrews’ last chance at independence until modern times.2

It was during this time that the effects of Lysias’ previous actions began to take root. Once Simon’s brother Jonathan was dead, the role of both king and High Priest fell to Simon. His son, John Hyrcanus followed in his footsteps, taking up the dual role as Simon had.3 Under Hyrcanus, the conquest and forced conversion of the Idumeans who lived in southern Israel. This conversion, conducted in a manner forbidden in Jewish law, would produce significant figures as rulers of Israel including Herod the Great.4 This confusion of the political leader and the religious leader of Israel brought about many changes in Israel, such as the rise of the Sadducees under Hyrcanus’ rule.5

Hasmonean Reform: The Ups and Downs

Of course, the period of Hasmonean rule was so influential because of several factors. Beginning with the Maccabees, religious reform was prominent under the Hasmoneans.6 For example, the incident that set off the Maccabean rebellion was the refusal of Judas Maccabee’s father, Matthias, to offer a sacrifice to a pagan god. Matthias, the priest of the village, instead killed the Jewish man who offered to take his place along with the Seleucid officers who were there to enforce the pagan ritual.7 Such violent and extreme reactions to pagan practices were common during the Maccabean revolt, further demonstrating the difficulties in Hellenizing the Jewish population. Such a focus on religious reform proved to be both beneficial and detrimental. While the culture of Israel and the traditions of the people were preserved through such resistance to outside influences, the inward focus on religion also gave rise to divisions within Jewish community. As Levine points out, “the emergence of Jewish sects - Pharisees, Sadducees, and Essenes (as well as the Qumran sect) - each with its own particular religious agenda, is a further indication of a more concerted Jewish emphasis at this time, at least within certain circles.”8 As the politics and religious traditions of Israel became intermingled in new ways during the Hasmonean era, the issue was further complicated by the rise to power of religious sects that were divided over key theological issues. The important aspect here is how the Hasmonean efforts at political and religious rule differed fundamentally from what had existed in Israel under the Davidic kingship.

While politics and religion had always worked together in Israel prior to the exile, the Hasmoneans adopted a system that borrowed more from the Greeks than the Classical era Hebrews. Evidence of this of this begins with John Hyrcanus, who adopted the Greek name Hyrcanus.9 The subsequent rulers did the same, adding Greek names to their Hebrew names. More evidence of this kind of influence can be seen through various events that took place within the court:

Hellenization in the Hasmonean court is likewise reflected by the hiring of foreign mercenaries and, more poignantly, by the assumption of royalty by Aristobulus and Alexander Jannaeus. Even more telling in this regard is the sole rule of a queen, as was the case with Salome Alexandra. This smooth and unchallenged succession was very likely facilitated by contemporary Ptolemaic practice.10

Such a mingling of cultures was something that proved favorable to the “priestly supporters of the Hasmonean dynasty,” namely the Sadducees.11

Forced Circumcision and Its New Testament Impact

The primary way that this confused concept of the High Priest and King offices manifested the forced conversion of the Idumeans under John Hyrcanus. After conquering the Idumean people in Southern Israel, Hyrcanus forced them to convert to Judaism which demanded circumcision. And Hyrcanus was not the last Hasmonean ruler to do so, “Judas Aristobulus I (104-103 BCE), did the same to the Itureans, an Arab tribe settled in Lebanon, the Golan, and the Galilee, and Aristobulus's successor, Alexander Janneus, seems to have continued the practice.”12 The precedent for such an act has roots in the early days of the Maccabean revolt, though with serious deviations. Weitzman examines 1 Maccabees against the writing of Josephus and Ptolemy to determine the nature of these violent episodes, and his conclusions are worth repeating:

while Mattathias had imposed circumcision on Jews, Hyrcanus and his successors extended this practice to Gentiles under their control. What impelled this adaptation, I am suggesting, was the tension between the Hasmoneans' increased reliance on Gentiles and those rulers' status as heirs to the Maccabean Revolt. The latter was crucial to Hasmonean legitimacy in the eyes of Jews, but the anti-Gentile policies required to sustain Hasmonean legitimacy also had the effect of limiting the supply of human capital available to the state . . . The forced circumcision of Gentiles can be read as an attempt to overcome this impasse, disguising the absorption of local non-Jews as a continuation of the Maccabean drive to retake the land for Judaism . . . The forced circumcision reports may represent a distorted account of history, masking Idumean and Iturean complicity or simplifying a complex process of cultural coalescence. The evidence indicates that these reports do preserve something authentically Hasmonean, however, by revealing how the dynasty tried to represent their reliance on local Gentiles to their Jewish constituency.13

Weitzman’s observation that the religious act of circumcising converts to Judaism had become a political practice demonstrate the oscillation and confusion that resulted from the Hasmonean rulers mixed office of High Priest and king. While other kings certainly used religious traditions to their advantage, no other dynasty was so confident of forcibly combining the two roles. The cultural impact was felt throughout from the time of John Hyrcanus to the destruction of Jerusalem in 70 A.D.14 The New Testament church struggled with required circumcision, evidenced by Paul’s argument against it in his letter to the Galatians. The implications suggest that the forced circumcision that became popular under the Hasmoneans transferred over to the Christian Jewish community.

Conclusion

While forced circumcision is not mentioned in the Gospel accounts, the effects of combining the political and religious offices through forced conversion remain hot topics in Christian studies. In Jesus’ own day, His most vocal opponents were those who hailed from the religious elite, varying from Sadducee to Pharisee to scribe. Constantly seeking to argue with Him, and often hoping to turn the crowd against Him, the Jewish leaders of Jesus’ day struggled with the same sense of “need” and “rule” that the Hasmoneans struggled with prior to their conquest by the Romans. The political aims and religious abuses of the Jewish leaders undoubtedly came to a head during the illegal and farcical trial against Jesus that eventually led to His crucifixion (cf. Matthew 26, Mark, 14, Luke 22, John 18). The uneasy alliance between politics and forced religion had taken its toll. The long-term effects of the forced conversion under Hasmonean rule did damage, not only to the offices they corrupted, but also to the Jewish cultural identity. When Paul writes against the Judaizers in Galatians 4-6, there are political implications that might be better understood if Protestants knew more about the Apocrypha.

Bibliography

Atkinson, Kenneth. A History of the Hasmonean State: Josephus and Beyond. London: Bloomsbury T&T Clark, 2016.

Cate, Robert L. A History of the Bible Lands in the Interbiblical Period. Nashville, TN: Broadman Press, 1989.

Eckhardt, Benedikt. “Reclaiming Tradition: The Book of Judith and Hasmonean Politics.” Journal for the Study of the Pseudepigrapha 18, no. 4 (2009): 243-263.

Lea, Thomas D., and David Alan Black. The New Testament: Its Background and Message. Nashville: Broadman & Holman Publishers, 2003.

Levine, Lee I. “Hasmonean Jerusalem: a Jewish city in a Hellenistic orbit.” Judaism: A Quarterly Journal of Jewish Life and Thought 46, no. 2 (Spring 1997): 140-146.

Regev, Eyal. The Hasmoneans: Ideology, Archaeology, Identity. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Reuprecht, 2013.

Weitzman, Steven. “Forced Circumcision and the Shifting Role of Gentiles in Hasmonean Ideology.” Harvard Theological Review 92, no. 1 (January 1999): 37-59.

This basic outline is a summary of chapter 2 in Atkinson’s A History of the Hasmonean State: Josephus and Beyond, 23-46.

Cate, 88.

Regev, 65.

Atkinson, 94; Regev, 275.

Regev, 151-158.

Levine, 141-142.

Atkinson, 26-27.

Levine, 142.

Levine, 144.

Levine, 144.

Lea and Black, 20.

Weitzman, 38.

Weitzman, 58-59.

The societal reaction towards the politicization of forced circumcision is arguably present in the book of Judith. Eckhardt argues that language seen in Judith is evidence that there was popular disagreement with the Hasmonean policy of forced circumcision. He writes,

1 Maccabees clearly emphasizes genealogy as a constitutive element of Israelite identity. The book of Judith now uses this very language for thirteen chapters—only to render it completely ineffective in ch. 14. The conversion of Achior demonstrates that archaizing language cannot determine Jewish identity. The use of this language in 1 Maccabees is delegitimized; the book of Judith questions the Hasmonean way of defining the Judaism they advocate through this language. Israelite tradition, according to Judith, is not represented by forced circumcision or genealogically restricted access to God’s holy people, but by Ruth the Moabite and Achior the Ammonite, who, without being forced to do anything and without any constructed kinship that might obscure the facts, joined the house of Israel, Ruth even playing a central role in the genealogy of David. The integration of an Ammonite into the house of Israel is a further case of reclaiming biblical tradition. In the fictive and ironical setting of the narration, it is possible to use the language of Hasmonean propaganda apart from the meanings ascribed to it by the framework of legitimizing discourses. It is even possible to use the same language and reach opposite conclusions . . . More important is the observation that Judith reclaims biblical tradition and language by altering the scriptural recourses used by 1 Maccabees. (259-260)

This would perhaps be evidence of the type of disgruntled attitude found in the New Testament towards the religious elite who held power. It can be argued that the mingling of political and religious offices after the return from exile had bothered the Jewish community for some time before Jesus arrived on the scene.