The Norman Conquest

Or, Why Should You Care About William the Conqueror?

This is the second of my “updated” essays. This one originated from my semester in Cambridge as an undergrad. I still think about the Norman Conquest often, almost twenty years later.

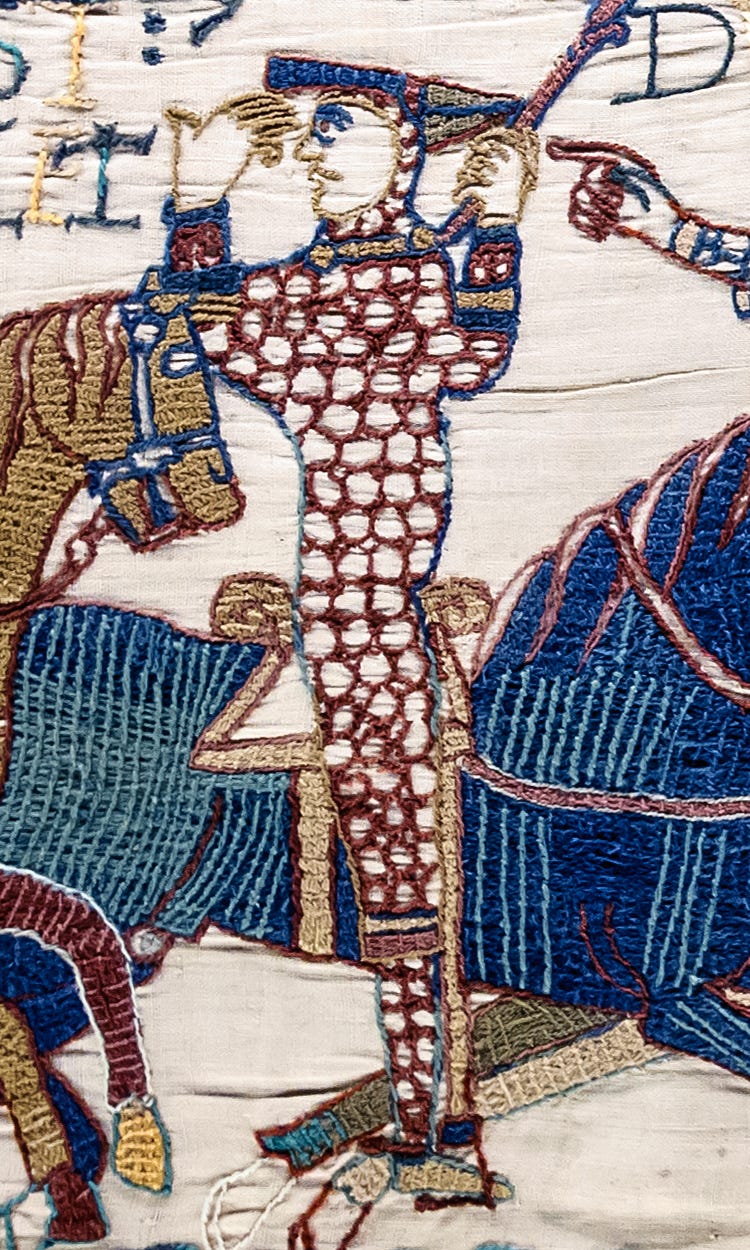

The formation of Anglo-Norman England was a milestone in history. William the Conqueror’s domination of both his Norman and English lands provoked cultural changes and international conflicts that left such imprints on the respective peoples that the effects are still debated today. This crucial moment in history was not one of tranquility or calm. The turbulence surrounding William’s reign over the two lands separated by the English Channel came from within and without. Just what posed a greater threat, an English rebellion or a foreign attack, is a question that provokes much discussion. In truth, no one form of attack was a single threat. It was the combined maneuvers of local and foreign rebels that might have overthrown the new regime in England. One must consider both alien and native attacks when looking at the Norman Conquest and in particular the rebellions between 1067 and 1071 and a final rebellion in 1075, the most significant of which were coordinated by foreigners and internal rebels.

There were in fact many perceived threats to William’s initial rule of the kingdom of England. Harold Godwineson, the last Anglo-Saxon king of England who died in the Battle of Hastings, had family who were able to rally support against William in 1068 and 1069.1 However, these rebellions qualified as nuisances at the most. Harold’s sons were never able to mount any significant threat, due in large part to their lack of foreign help. Even some of the English did not support Harold’s family, perhaps because he was not next in line to Edward the Confessor’s crown from the beginning.2 Whatever the reason, Harold’s descendants nor any other Englishman could mount any sizeable threat to William’s occupation and rule of England. The few thegns who did attempt to force the Normans out resorted to guerilla warfare, but William did not treat them as something that needed immediate suppression.3 This lack of ability to unite squashed England’s internal rebellions, but the rebels found help whenever foreigners became involved in some form.

The first significant rebellion against William’s Norman rule took place in the summer of 1067 and “focused on Dover, centre of the oppressive [Bishop] Odo’s operations.”4 The native rebels, primarily from Kent sought the help of Eustace of Boulogne to seize Dover. Eustace had supported William in 1066 and this change in loyalty would become normal among William’s allies over the next ten years. Here, the French and English allied themselves against the Normans, and this conglomeration formed a pattern for future rebellions in both their organization and their eventual outcome

.

Similar battles broke out in the north, with William’s own men siding with local threats. Orderic Vitalis referred to these rebellions as the result of “greedy Normans.”5 These smaller threats culminated in the rebellion of 1069 that saw William’s foes all unite. The Danish King Sweyn allied himself with Edgar Aetheling and King Malcolm of Scotland. This momentous attack, which commenced in York, was however driven back by King William himself. He arrived to relieve the garrison that had been under siege in York and built a second castle which would be placed under the command of William Fitz Osbern. Shortly after this, many rebellions began to spring out all over the north, inspired by the Scottish and Danish help thought to be arriving to help.6 In response to this constant turmoil, William unleashed a furious act now known as ‘the Harrying of the North.’ As William destroyed much of the countryside of northern England, be not only drove back the foreign invaders, but he also broke the English will to be free in many ways. This pattern of military conquest also gave William to rid himself of the English nobles Edwin and Morcar, two men who had originally sworn loyalty to William, but had been provoked to rebellion, more than likely by the same “greedy Normans” that Orderic wrote of.7

The years of 1070 and 1071 saw both a tumultuous pattern of local rebellion but also saw the beginning calm of English submissiveness to the new King. According to many sources, Orderic Vitalis for example, the merging of the Anglo-Saxon and Norman cultures took place at a fast and efficient pace. By the year 1070, Vitalis saw the Anglo-Norman nation as a peaceful, just land, although “unhappily this was not to last.”8

In 1075, the last significant English rebellion was begun. This time, the English allied with Norman, Breton, and Danish armies to oust the Conqueror. The Earls of Norfolk and Hereford allied themselves to regain some of the lands their fathers had held in years prior to the 1070 revolts. Ralph, the earl of Norfolk was a Breton, and sought help from the continent. Regardless, however, of the size of the rebellion, it was dispatched quite speedily. Lanfranc, the Norman archbishop of Canterbury, rose up to oppose these rebels and succeeded with amazing military leadership. The only major invasion that resulted from this final rebellion was again in the north as the Danish King Cnut sacked York Minster. After the sacking of the town, the Danes simply retreated to Flanders and did not truly pose any more threat to William’s rule.9

In examining the Conquest, it is important to understand that military prowess did not prove to be William’s only vital ability. William’s true power came in the form of the English government that had been established prior to the Conqueror’s invasion. William, instead of imposing a French idea of government, simply used the already established forms to maintain a tight control over the English in normal ways. He appointed Normans as lords, even having them serve next to English nobles in local court cases to promote assimilation between the two peoples.10 Excerpts like those from the English Historical Documents show that William was an exceptional administrator as well as a grand military leader. And since “the basic structures of Anglo-Saxon government [were] superior in many ways to those in Normandy,” William’s decision to simply utilize them played a large role the ineffectiveness of England’s various rebel attempts.11 William’s ability to stand out as a figurehead also directly contrasts the fact that England was never able to rally behind a single person. Each rebellion saw the rise of another rebel leader and thus continued the disjointed efforts by the English to restore some form of a native leader to the kingship.

The rule of King William, in many ways, was never something that the English truly contested. His ability to put down revolts, either through his Norman lords put in place throughout England or by his own presence, was fast and incredibly effective. William’s ‘Harrying of the North’ demonstrated the lengths to which he would go quickly to unite his new kingdom and end the rebellious attacks that were becoming a nuisance to him. However, a nuisance is all the revolts truly were to William. With most casualties on the English side, it made no sense for the local people to continue to resist the only leader that they had. The chronicler, Orderic Vitalis, is a witness to the speed with which Anglo-Saxon and Norman racial hatreds subsided, since he was of a Norman father and an English mother and was born in 1075. The Norman conquest of England was a fast and efficient change of government. But the impact of the change of regime that began in 1066 is far flung and is in no way limited to a few short years. Most significantly, it was the peaceful administration of the English that gave William the power to rebuff all attacks on, and within, his island nation. The English in many ways simply served William from the moment he landed on their shores, effectively allowing the rise of the new Anglo-Norman kingdom that would challenge not only their neighbors but also the entire world.

Works Cited

Carpenter, David. The Struggle for Mastery: The Penguin History of Britain 1066-1284. London: Penguin Books Ltd, 2004.

Douglas, David C. William the Conqueror. London: Yale University Press, 1999.

Golding, Brian. Conquest and Colonisation: the Normans in Britain, 1066-1100. New York: Palgrave, 2001.

Vitalis, Orderic. “Volume II, Books III and IV.” In The Ecclesiastical History of Orderic Vitalis. Ed. and Trans. Marjorie Chibnall. Oxford: Clarendon P, 1990.

Young, G. M., and David C. Douglas, eds. “Government and Administration.” In English Historical Documents, 1833-1874. Ed. W. D. Handcock. New York: Routledge, 1995.

Douglas, 183; Golding, 38.

Carpenter, 61.

Golding, 37.

Golding, 38.

Qtd. in Douglas, 76.

Golding, 40-41.

Golding, 45.

Vitalis, 257.

Golding, 43-48.

Young, 484-485.

Carpenter, 90.