The Problem of Ursula

Or, Why Thundercats Was More Important Than We Thought

This first post is a brief piece of cultural commentary. I don’t know how often I’ll get around to things like this, but when the Muse strikes . . .

The recent Disney remake of The Little Mermaid has been hit with a conflagration of praise and criticism. It seems destined to fail in pleasing either of its intended audiences: movie critics of a left-leaning stripe and young children interested in seeing a “modern” version of the 1989 animated film.

There are plenty of folks claiming that the bad reviews come from bad actors and there are others hoping to find evidence of current cultural wars. To boot, as the remake approached release, the history of Ursula’s design, drawing from drag queen influences, made headlines (which, fittingly, was seen alternatively as a sign of diversity and also a lack thereof). Most of this will boil down to nada, much like the fervor over Disney’s previous live action remakes. Who is still talking in earnest about Cinderella (2015) or The Jungle Book (2018)? Even Aladdin (2019) only comes up when one of the actual actors says something controversial. Overall, the live action remake trend doesn’t seem to prompt the kinds of films that linger, those which live in the corners of one’s memory for years to come. And this is true even when they’re decently made.

The Little Mermaid (2023) has made waves in one peculiar way though. Both the positive and negative reviews have made much over some of the changed lyrics. When first announced, the positives of having Lin Manuel Miranda contribute were highlighted, and the fact that 2023 and 1989 are not the same time culturally speaking was referenced often. One of the things I found most interesting was a strong consistency: every review I’ve seen highlights a specific omitted verse from the 1989 version of Ursula’s “Poor Unfortunate Souls.”1 It is the heart of the original tune:

The men up there don't like a lot of blabber

They think a girl who gossips is a bore

Yes, on land it's much preferred

For ladies not to say a word

And after all, dear, what is idle prattle for?

Come on, they're not all that impressed with conversation

True gentlemen avoid it when they can

But they dote and swoon and fawn

On a lady who's withdrawn

It's she who holds her tongue who gets a man

Alan Menken, who composed the original verse, has pointed out that it is manipulative by design. Others have highlighted the “problematic” nature of “silencing women” through a catchy tune. But the insight that has been most on the nose I found in a review by Sara Stewart at CNN:

in my experience, kids are very good at knowing not to take a cartoon villain’s advice at face value.2

As many reviews have noted, softening Ursula’s cynicism doesn’t seem to improve the film; isn’t the point that Ursula is the bad guy? Which does make one wonder: why doesn’t Disney understand this? It seems a no brainer that the villain ought to be, well, evil. Perhaps it is because they have made a business out of wanting children to trust villains? After all, Maleficent is merely misunderstood, and her descendants proved she just needed more love in her heart. And don’t even try to make sense of the many redemption arcs in Once Upon a Time. Villains are just people too, seems to be the message.

What balderdash.

There is a place for films to do something other than pit good guy versus bad guy, for sure. Some of Disney’s best recent films, Encanto and Moana for example, have actively omitted any real villain.3 But whether Disney as a company knows what it is doing, there has been a real push for children to sympathize with evildoers rather than recognizing them as evil. Such shifts in storytelling suggest a retreat, an unwillingness to recognize that children’s stories can and sometimes ought to contain the defeat of evil.

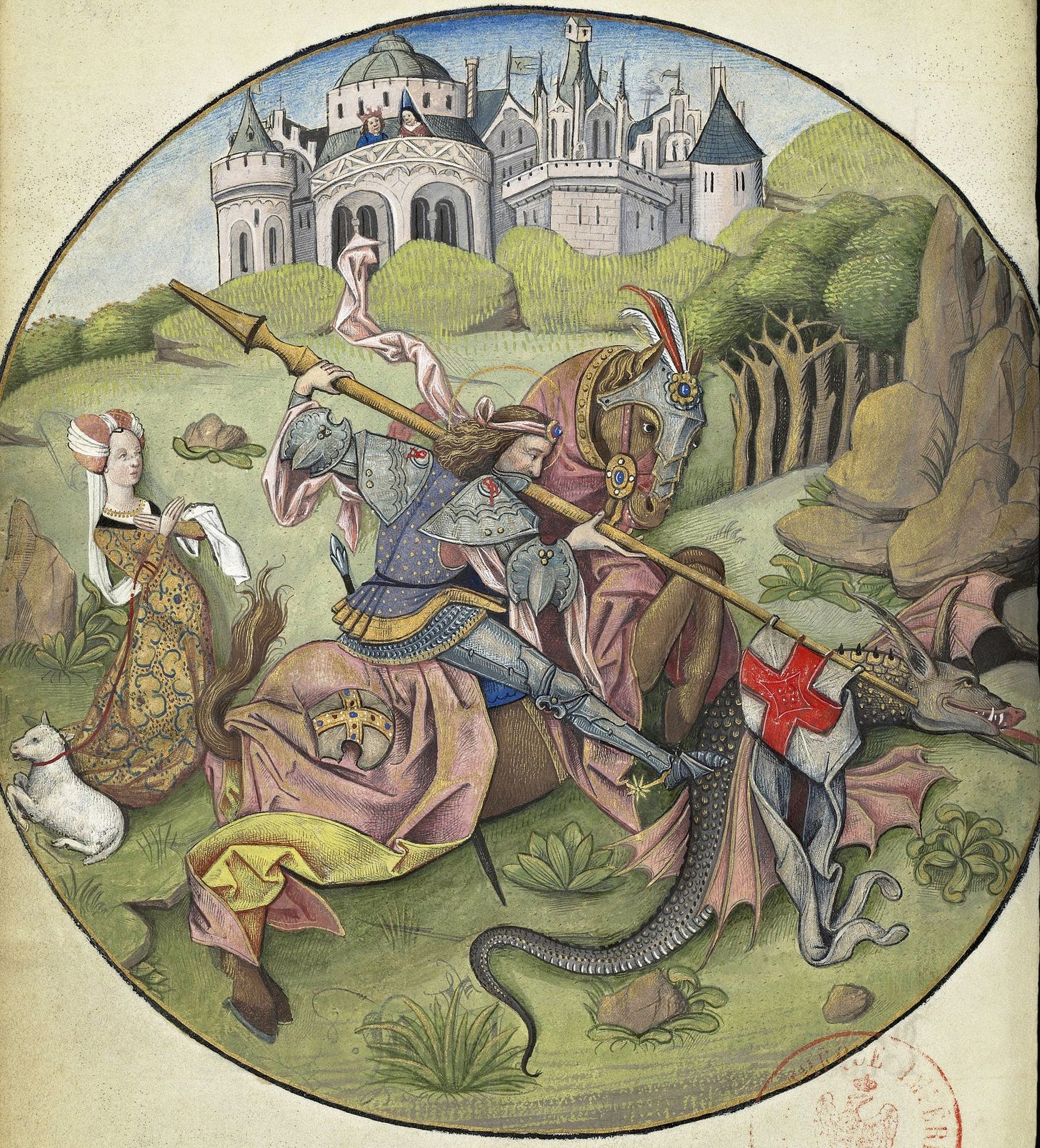

Not that this is new. G. K. Chesterton hit on this in Tremendous Trifles way back in 1909:

Fairy tales do not give the child his first idea of bogey. What fairy tales give the child is his first clear idea of the possible defeat of bogey. The baby has known the dragon intimately ever since he had an imagination. What the fairy tale provides for him is a St. George to kill the dragon.

Despite not being new, this is the thing that Disney executives, and many others in our culture, fail to understand: children already know that good and evil exist. One of the most important things they can be given is stories which will show them that evil can be defeated.

Strangely, cartoon executives did know this once upon a time, even if they didn’t understand it. Companies like Mattel did research in the 80s, discovering that young boys were preoccupied with good versus evil prior to any cartoon influence. It was as if this were their natural state. The results didn’t strike anyone as odd in the 1980s though, and companies like Hasbro and Mattel decided to capitalize on this natural inclination to increase sales. Thus, cartoons like He-Man and Transformers hit airwaves primarily to sell toys, but the success of the cartoons and the toys depended on standard story-telling concepts to make their products compelling.4

One of these shows demonstrates just how true Chesterton’s thought rings. ThunderCats ran for four seasons from 1985-1989, and neither of its attempted reboots have had much success.5 The premise of the original show pitted the good guys, the ThunderCats and their friends, against the bad guys, the Mutants and their sometimes ally Mumm-Ra. Nothing could have been plainer than good versus evil in this show. To get ready for battle, Mumm-Ra literally called upon the forces of evil to aid him:

Ancient spirits of evil, transform this decayed form to MUMM-RA, THE EVER-LIVING!

Sure, the show had hokey themes and cheesy conclusions, but the sides were always clear. It was so certain that good would triumph because evil was defined. Children argued over who got to be Lion-O in this round of pretend, not Slythe. It didn’t even matter if the bad guys had the upper hand or were sometimes stronger than the good guys; evil simply could not win in the end. Consider the 25th episode of the show, where the leader of the ThunderCats defeats an all-powerful Mumm-Ra by showing him his reflection:

Mumm-Ra: Nothing can stop the vengeful force of Mumm-Ra!

Lion-O: Except, evil Mumm-Ra, the horror of your own reflection!

Examples like this used to be the norm. Sure, there were always outliers and artists who wanted to kick against the norms,6 but such expression was limited by what company heads knew: tradition matters. And this kind of defeat, where children are assured that there is a St. George to kill the dragon, that a manipulative villain won’t succeed in the end, is still a key fabric in our culture, even if companies like Disney want to deny it. The continuation of the tradition that sought to reinforce the bend of young men to desire the evil’s defeat won’t go away because song lyrics are changed.

The Little Mermaid (2023) is a powerful reminder that though the sensibilities of executives and writers might change, the democracy of the dead still speaks loudly.7 And while today’s Ursula might still die at the end, her death is not something to be celebrated if no one can state that the plain fact that every dragon must be slain.

UPDATE: Apparently, Tom Smyth at Vox had similar thoughts. I’m not sure his argument goes deep enough, but I might return to this idea later since it seems to be a common enough critique.

I wouldn’t be surprised if there is at least one that doesn’t mention this specifically, but I have not witnessed it yet.

Most of Stewart’s critiques fall into the aforementioned categories, but this one stood out to me.

This isn’t a knock against these films, but an observation. Disney seems to struggle in the present time to create a meaningful children’s film if a genuine, singular villain is involved.

This was true of girls as well, though the emphasis was slightly different. Shows like Jem and My Little Pony still had clearly defined villains, but those conflicts were not the emphasis of the shows. Todd Gitlin, Watching Television: A Pantheon Guide to Popular Culture (New York: Pantheon Books, 1986), 77-78.

The first reboot ran for only a single season, ThunderCats (2011-2012), as did the second, ThunderCats Roar (2020). In comparison to the reboots of other cartoons from the same era, such as Voltron: Defender of the Universe (1984-1986) and Masters of the Universe (1982-1988), and their respective reboots Voltron: Legendary Defender (2014-2018) and Masters of the Universe: Revelations (2021-), a single season reboot is immensely disappointing.

Kevin Eastman and Peter Laird disliked the cartoon version of their comic, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, and its lighter, comic tone. And yet, it remains the cartoon that continually sees new renditions and high sales. Cf. https://www.mentalfloss.com/article/30862/complete-history-teenage-mutant-ninja-turtles

“Tradition means giving votes to the most obscure of all classes, our ancestors. It is the democracy of the dead. Tradition refuses to submit to the small and arrogant oligarchy of those who merely happen to be walking about. All democrats object to men being disqualified by the accident of birth; tradition objects to their being disqualified by the accident of death. Democracy tells us not to neglect a good man's opinion, even if he is our groom; tradition asks us not to neglect a good man's opinion, even if he is our father. I, at any rate, cannot separate the two ideas of democracy and tradition; it seems evident to me that they are the same idea. We will have the dead at our councils. The ancient Greeks voted by stones; these shall vote by tombstones. It is all quite regular and official, for most tombstones, like most ballot papers, are marked with a cross.” —G. K. Chesterton, Orthodoxy (London: The Bodley Head, 1909), 85-86, emphasis added.